#14: Tracing the Sources of Bernard de Montfaucon’s ‘Maffei‘ Gems

Luisa Siefert

Version of the article suitable for citation

on ART-Dok (Heidelberg University Library)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00009841

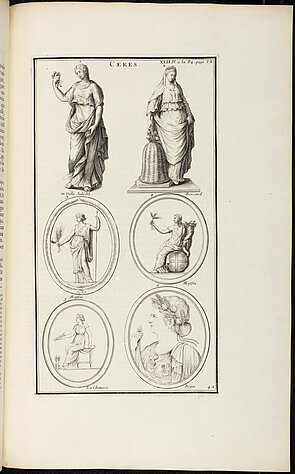

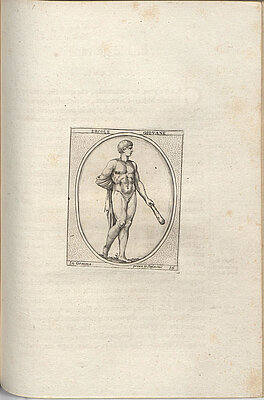

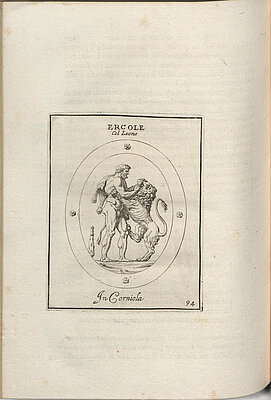

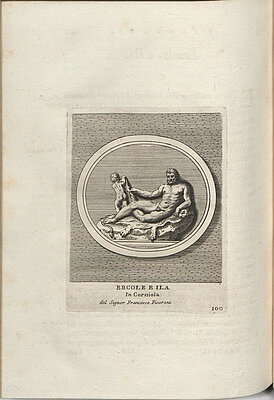

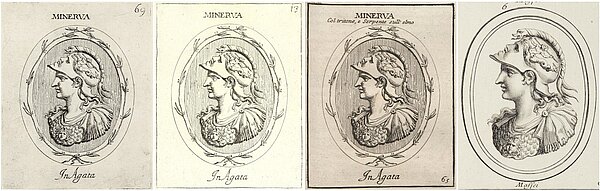

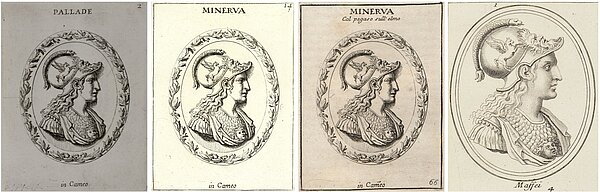

The engraved gemstones in the illustrated catalogue L’antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures (1719), curated by Bernard de Montfaucon (1655–1741), and in its accompanying Supplément volumes (1724), can usually be easily identified by their distinctive oval double frames even though they are often shown in an abstract and enlarged form (fig. 1; ThesaurusID 23881044). As Montfaucon’s compilation does not arrange ancient – or supposedly ancient – artworks by genre but instead foregrounds pictorial motifs and themes, the engraved gems assume a newly defined and thus equal position among altars, statues, reliefs, candelabra bases, cylinder seals and coins. Questions of materiality or of a more precise classification, whether the gemstones are incised intaglios or raised cameos, are of little significance in this context. The following discussion therefore adopts the general term gem to refer to them. [1]

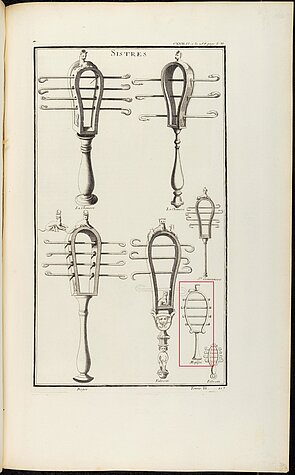

And even though an oval frame is not always a reliable indication – as illustrated by the depiction of an unframed sistrum (fig. 2; ThesaurusID 1467968) –, a consistent piece of information shared by all of Montfaucon’s gem illustrations is the indication of his source. This makes visible the models from which Montfaucon had his illustrations copied. In addition to sources indicated as ‘Beger‘, ‘La Chausse‘, or ‘Capello‘, the designation ‘Maffei‘ appears in a total of 214 gem illustrations. This particular group of sources receives special attention in the following discussion.

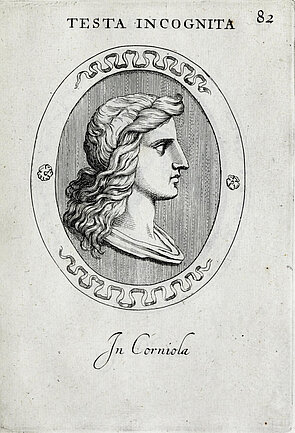

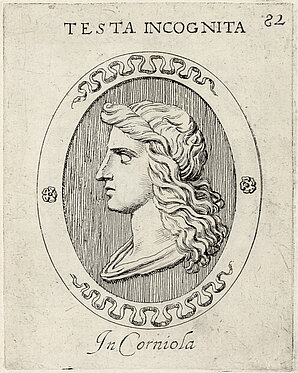

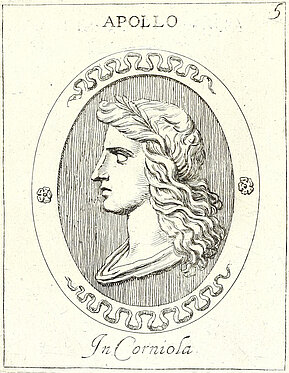

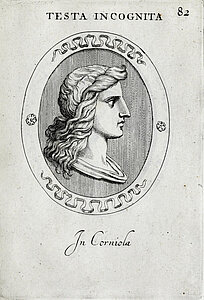

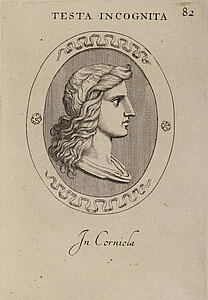

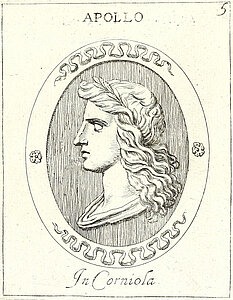

From Montfaucon to his Source Maffei

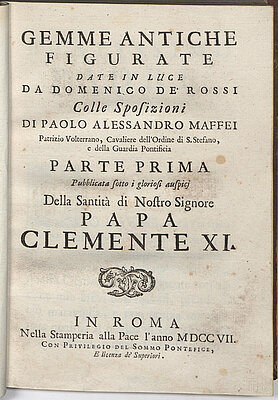

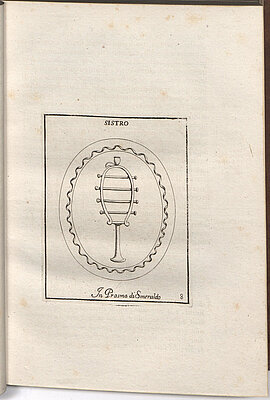

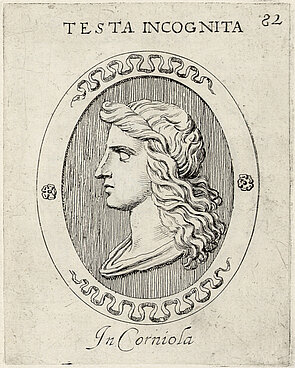

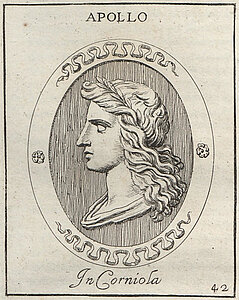

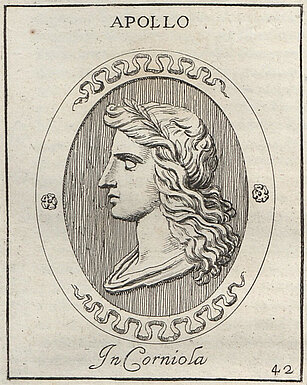

Virtually all the illustrations attributed to ‘Maffei‘ have counterparts in the four-volume book Gemme antiche figurate (fig. 3; ThesaurusID 1315438) by the Italian antiquarian Paolo Alessandro Maffei (1653–1716), which Montfaucon therefore used extensively as a model for the depiction of engraved gemstones. A few years before the publication of L'antiquité expliquée, Maffei had published Gemme antiche figurate between 1707 and 1709 in collaboration with his Roman publisher Domenico de’ Rossi. [2] As its title suggests, the four volumes contain over 400 illustrations of gemstones, each accompanied by descriptive text. They provide a thematically organized survey of historical portraits, including kings, consuls, and emperors with their consorts, philosophers, historians, and lyric poets, teste incognite, as well as mythological figures, ritual scenes and implements, theatrical masks, and animal motifs. In contrast to Montfaucon’s later method of illustration, Maffei allocated a separate page to each gemstone. Each page also specifies the material of the stone, such as ‘In Corniola‘, ‘In Onice‘, or ‘In Prasma di Smeraldo‘, at the base of the rectangularly framed illustration, along with an explanatory title, for example, ‘ISIDE E SERAPIDE‘, ‘ERCOLE‘, or ‘SISTRO‘ (fig. 4; ThesaurusID 1551643).

Montfaucon’s reference to ‘Maffei‘, along with the availability of the corresponding illustrations in Maffei’s Gemme antiche figurate – each provided without further information on the origin of the prints – initially gives the impression that Maffei’s work is the original source of these depictions. This, however, is misleading. In fact, only some of the engravings were newly created for Maffei’s books; the vast majority are a curated compilation drawn from earlier publications.

Montfaucon is therefore not wrong in citing ‘Maffei‘ as his source, yet his reference reveals only part of the truth regarding the original provenance of the images. Following the methodological approach of the Antiquitatum Thesaurus, this provenance will now be examined in detail.

From Maffei to Agostini

The diverse sizes and styles of the more than 400 gem illustrations in the four volumes is not the only evidence of a compiled collection of various older publications (figs. 5–8).

In the introductory text to his first volume, Maffei offers al cortese lettore insights into the creation and compilation of his Gemme antiche figurate. In the very first sentence of this preface, Maffei mentions that the impetus for producing his extensive work was the recent acquisition of outstanding copper plates by his publisher Domenico de' Rossi, which immediately inspired Maffei to publish them in a new manner in his own books. [3]

The acquired copper plates had originally been created by the Florentine etcher Giovanni Battista Galestruzzi (c. 1615–1669) for the archaeologist and numismatist Leonardo Agostini (1594–1676). Agostini served as antiquarian to Cardinals Bernardino Spada and Francesco Barberini, as commercial advisor to Leopoldo de’ Medici, and as Commissario delle Antichità in Rome and the surrounding region of Lazio under Pope Alexander VII. [4] In 1657 and 1669, Agostini had the copper engravings printed for the two volumes of his catalogue Le gemme antiche figurate, in which he presented not only his own collection of gems but also selected stones from other prominent collections, such as those of Francesco Boncompagni and Cassiano dal Pozzo. [5]

The first volume, published in 1657, contains as many as 214 plates, whereas the second, from 1669, includes only 53. In both volumes, the etched illustrations are accompanied in the appendices by explanations and commentary from Giovanni Pietro Bellori (1613–1696). Agostini highlights the exceptional significance of his gem collection to the amico lettore, praising it as a source of artistic inspiration for highly esteemed painters and sculptors such as Raphael, Giulio Romano, Michelangelo, and Polidoro da Caravaggio. [6]

Reprints and Copies

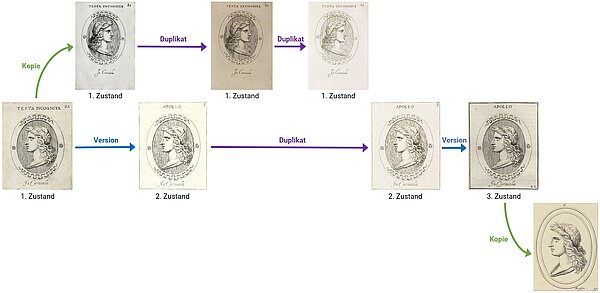

The wide circulation of the gems in printed form is demonstrated by the numerous reprints and copies of Agostini’s work in the years that followed, even before Maffei prepared his new edition in 1707. The ways in which the individual plates and the depicted gems were modified and underwent changes can be exemplified by the portrait of a young man.

First, in 1685, an edition translated into Latin by the Dutchman Jacobus Gronovius was published in Amsterdam. While it mirrors Agostini’s edition in scope and in the division of 257 plates across two volumes, it features reversed etchings produced by Abraham Blooteling, who also acted as the publisher [7] Abraham Blooteling (figs. 9 and 10). [8]

A parallel edition of the same work was published in the same year by Daniel van Gaasbeeck in Lugdunum Batavorum (Leiden). [9]

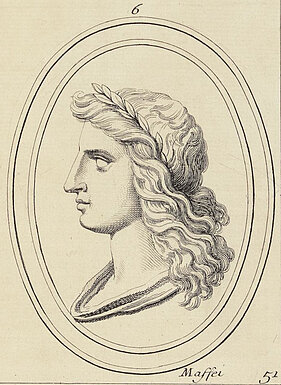

In 1686, Giovanni Battista Bussotti’s publishing house in Rome issued a second, revised edition of Agostini’s original copper engravings under the original title Le gemme antiche figurate di Leonardo Agostini, this time entirely curated by Giovanni Pietro Bellori. [10] Bellori, together with Giovanni Battista Marinelli, Michel’Angelo de Marchis, and Luca Corsi, was one of the four executors of Agostini’s estate, and Agostini had entrusted him with the copper plates of Gemme antiche figurate, requesting that Bellori, in collaboration with Marinelli, bring out this new edition. [11] Both complied, with Marinelli contributing only the preface, while Bellori oversaw the revision of the two volumes. [12] In the new edition, Bellori not only redistributed the material more evenly across the two volumes, resulting in 115 plates in the first volume and 151 in the second, but also reorganized and renumbered all plates, finally addressing the imbalance in Agostini’s original edition, where the first volume contained 214 plates and the ‘scarso & inferiore‘ [13] second only 53 plates. [14] Moreover, Bellori modified the captions of several plates, for instance changing ‘PANE‘ to ‘SATIRO‘ or ‘DEIANRIA‘ to ‘ONFALE‘, and in some cases even altered the images themselves. This is illustrated by Agostini’s ‘TESTA INCOGNITA‘ (fig. 9a; ThesaurusID 23933961), where Bellori added a laurel wreath, transforming the portrait of the already mentioned unknown young man into ‘APOLLO‘ in the revised edition (fig. 11; ThesaurusID 23937056).

In 1694 and 1699, a second and third edition of Jacobus Gronovius’ Latin version with the reversed etchings by Blooteling were issued, now published by Leonardus Strik in Franeker in the Netherlands. These editions differ from the previous version only in the revised initials at the beginnings of the texts, while the plates were printed from the unchanged copper plates (figs. 10a, 12 and 13). [15]

In 1702, the Roman publishing house of Giuseppe Monaldi issued an edition in honour of the Príncipe de Santo Buono Carmine Nicolao Caracciolo. Apparently, Monaldi had come into possession of Bellori’s revised copper plates from 1686 and reused them in the same condition. In any case, no differences can be observed in the gem illustrations compared to that edition (figs. 9b, 11a and 14). [16]

Even though the Dutch copies in particular bear little relation to Montfaucon’s sources, this overview of new editions, reprints, and copies of the copper plates originally created by Galestruzzi offers a clear picture of the wide circulation of these illustrations during the fifty years between the publication of Agostini’s and Maffei’s respective Gemme antiche figurate.

Maffei‘s Version

In contrast to the editions mentioned above, Maffei undertook a far more extensive revision of Bellori’s 1686 edition of Agostini’s Gemme antiche figurate. To this substantial core of 253 plates, he added a number of plates that had long been held in De’ Rossi’s collection from the series of engravings after the gems of the sixteenth-century Grimani collection – comprising 38 plates – as well as three plates first published in 1627 by Pietro Stefanoni. [17] These reprints of copper plates acquired by De’ Rossi were further supplemented by 121 entirely new engravings by Francesco Faraone Aquila (c. 1676–1740), depicting additional gems from Roman and other collections. While the Aquila, Stefanoni, and Grimani gems were explained solely through Maffei’s sposizioni, in his commentary on Agostini's gems he first provided the descriptions and notes written by Bellori in italics (‘per non defraudare il Bellori, o sia l’Agostini, della gloria acquistatasi in quest’opera‘ [18]), and then supplemented them with his own osservazioni.

Since Maffei rearranged the plates taken from Bellori's Agostini edition within his four-volume work, he had them renumbered and, in some cases, also changed the captions. The ‘APOLLO’ now appears unchanged in the image, but with a newly reinforced frame on plate 42 of the Parte seconda (figs. 9c, 11b, 14a and 15; ThesaurusID 23925596). [19]

From Agostini, Bellori, and Maffei to Montfaucon

In contrast to Maffei, Montfaucon was neither able nor willing to draw on existing copper plates for his L’antiquité. Instead, he selected, copied, and composed all the motifs for his more than 1,100 plates in the manner described above (fig. 15a; ThesaurusID 23925596 and fig. 16; ThesaurusID 23919968).

According to the research summarised here, of the total of 214 gem illustrations with the source reference ‘Maffei’, 102 are based on illustrations that Giovanni Battista Galestruzzi had produced for Leonardo Agostini sixty-two and fifty years earlier, respectively. [20] Since their first use in 1657 and 1669, the copper plates have undergone various states and reproductions over the years until Montfaucon made his copies in 1719 (fig. 17).

Tracing the engravings back to Agostini also makes it possible to identify some – currently around 73 – of the 214 gems depicted by Montfaucon in today's collections: A large part of Agostini's former gem collection is now housed in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze and the Tesoro dei Granduchi in Florence, after Agostini was able to sell a large part of his collection to Cardinal Leopoldo de' Medici with the help of Ottavio Falconieri shortly before his death around 1670. [21] These include, for example, an intaglio and a cameo, each with a portrait of Athena (figs. 18–22; ThesaurusID 24010504 and figs. 23–27; ThesaurusID 24010516).

The value of tracking down and closely examining the previous printed versions of the individual illustrations is impressively demonstrated by Montfaucon's ‘Apollon’. Ultimately, the ‘Apollon’ owes his appearance neither to Montfaucon’s direct copy from Maffei nor to Agostini's original version, but to Giovanni Pietro Bellori's laurel wreath crowning the former ‘testa incognita’. Whether this intervention was justified will hopefully become clear when the gem is eventually identified in Florence (or elsewhere).

[1] For his support and valuable suggestions, I would like to thank Timo Strauch. For a differentiation of the terms gem, intaglio, and cameo, see Erika Zwierlein-Diehl: Antike Gemmen und ihr Nachleben, Berlin 2007, pp. 4–5; most recently also Angelika Marinovic: ‘“da una quantitá tanto picciola, quanto appena è visibile”. The small format of ancient gems as a challenge and a characteristic feature in print depictions from the first half of the sixteenth century’, Pegasus. Beiträge zum Nachleben antiker Kunst und Architektur, 1, 2025, URL: https://doi.org/10.60604/pega.2025.1.110467 (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[2] The name ‚Maffei‘ appears more frequently in Montfaucon’s references, as he also copied plates from Maffei’s Raccolta di statue antiche e moderne, published in 1704. However, he usually labels these illustrations, in contrast to those from Gemme antiche figurate, with the designation ‚Raccolta Maffei‘.

[3] Paolo Alessandro Maffei: Gemme antiche figurate, 4 vols., Rome 1707–09, Parte prima (1707), p. xiii, URL: http://polona.pl/item-view/5eb394b4-a676-4858-acba-59089bbd06bc/0/827af8d0-1d01-47bd-a4a1-2b2d87961b0f (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[4] Margaret Daly Davis: Ten Contemporary Reviews of Books on Art and Archaeology by Giovan Pietro Bellori in the Giornale de’ letterati, 1670–1680, no. 1, Heidelberg 2008 (FONTES. Text- und Bildquellen zur Kunstgeschichte 1350–1750, 11), p. 26, URL: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2008/491 (last accessed 17 September 2025); Riccardo Gennaioli: ‘Una passione dinastica. Leopoldo de’ Medici collezionista di oggetti in pietre dure e di gemme‘, in: Valentina Conticelli, Riccardo Gennaioli, Maria Sframeli (eds.): Leopoldo de’ Medici. Principe dei collezionisti (exhibition catalogue, Florence 2017–18), Livorno 2017, pp. 145–175, here p. 153; Elena Vaiani: ‘La collezione d'arte e antichità di Leonardo Agostini: nuovi documenti‘, in: Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, Classe di Lettere e Filosofia, Series IV, Quaderni, 2, Pisa 1998, pp. 81–110, here p. 81.

[5] Gennaioli 2017, p. 154.

[6] Leonardo Agostini: Le gemme antiche figurate di Leonardo Agostini senese, Rome 1657, p. 3:‘Laonde all'età nostra, sono pregiatissime, nel consenso di tutti gli eruditi, & nelle lodi attribuitegli da Pittori, & da Scultori, havendo Raffaele da Urbino, Giulio Romano, Michel'Angelo Buonaroti, & Polidoro ritrovato in così piccoli esempi, argomenti grandissimi della loro arte.‘ URL: https://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/id/PPN638843030?tify=%7B%22pages%22%3A%5B5%5D%2C%22view%22%3A%22%22%7D (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[7] Blooteling evidently worked both as an engraver and as a publisher, as he and his brother-in-law requested a publishing privilege from the State of Holland in 1684; see Gregor M. Lechner: ‘Bloteling, Abraham‘, in: Andreas Beyer, Bénédicte Savoy, Wolf Tegethoff (eds.): Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon – Internationale Künstlerdatenbank – Online, Berlin/New York 2021, URL: https://www.degruyterbrill.com/database/AKL/entry/_10129546/html (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[8] Jacobus Gronovius (ed.): Gemmae et sculpturae antiquae depictae ab Leonardo Augustino senensi and Gemmae antiquae depictae per Leonardum Augustinum, 2 vols., Amsterdam: Apud Abrahamum Blooteling 1685, URL: https://archive.org/details/gemmaeetsculptur00agos_1 (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[9] Jacobus Gronovius (ed.): Gemmae et sculpturae antiquae depictae ab Leonardo Augustino senensi and Gemmae antiquae depictae per Leonardum Augustinum, 2 vols., Lugdunum Batavorum (Leiden): Apud Danielem à Gaesbeeck 1685, URL: https://stabikat.de/Record/787204102 (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[10] Leonardo Agostini: Le gemme antiche figurate di Leonardo Agostini, seconda impressione, 2 vols., Rome: Appresso Gio. Battista Bussotti 1686, URL: https://archive.org/details/legemmeantichefi01agos (vol. 1), URL: https://archive.org/details/legemmeantichefi02agos (vol. 2) (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[11] Vaiani 1998, p. 86; Donatella Livia Sparti: ‘Giovan Pietro Bellori and Annibale Carracci’s Self-Portraits. From the Vite to the Artist’s Funerary Monument‘, in: Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 45, no. 1/2 (2001), pp. 60–101, here pp. 60–61, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27654540 (last accessed 17 September 2025). ). The copper plates of the Gemme antiche figurate remained in Bellori's possession until his death in 1696, whereby he stipulated in his will that the plates should be granted to the heirs, who were still to be determined as legitimate: ‘Item lascia, vole, ordina e commanda, che l‘infrascritti suoi heredi non manchino di restituire li rami figurati delle Gemme Antiche, e scudi quarantacinque retratti da libri stampati con li medesimi rami havuti da esso Sig.re Leonardo Agostini senese quai restitutione doverà farsi à chi s‘aspetta di ragione con decreto del giudice.‘ Quoted in Sparti 2001, p. 100.

[12] Marinelli summarises in his preface to the 1686 edition Agostini’s last will and the circumstances surrounding the publication: ‘La qual cura di commune consentimento fu data al Sig. Bellori istesso, à lui convenendosi tale impiego, così per la sua insigne eruditone, come per esserne egli l'Autore; onde nella nuova editione havesse havuto facoltà di aggiungere, diminuire, e corregger le cose, come sue proprie, e render l’Opera più ricca, più corretta, e meglio ordinata.‘ Giovanni Battista Marinelli: ‘A chi legge‘, in: Agostini 1686, pp. 7–8, here p. 8. URL: https://archive.org/details/legemmeantichefi01agos/page/8/mode/1up (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[13] Ibid., p. 7. URL: https://archive.org/details/legemmeantichefi01agos/page/7/mode/1up (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[14] As Marinelli explains in the same place: ‘Per supplire à tal mancanza, fù suo proponimento il ristampare tutta l’Opera: e dividerla di nuovo in due parti, raccogliendo nella prima tutte le Teste degli Dei, degli Eroi, e degli altri Personaggi lllustri, e nella seconda tutte le figure di varie eruditioni, con dispositione più scelta, e più ordinata. Nel qual modo, l’uno, e l'altro Libro, diviso quasi con ugual portione, haverebbe ricevuto la sua giusta misura e grandezza.‘ URL: https://archive.org/details/legemmeantichefi01agos/page/7/mode/1up (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[15] Jacobus Gronovius (ed.): Gemmae et sculpturae antiquae depictae ab Leonardo Augustino senensi and Gemmae anti-quae depictae per Leonardum Augustinum, 2 vols., Franeker: Apud Leonardum Strik 1694, URL: https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.3484 ((last accessed 17 September 2025). Jacobus Gronovius (ed.): Gemmae et sculpturae antiquae depictae ab Leonardo Augustino senensi and Gemmae antiquae depictae per Leonardum Augustinum, 2 vols., Franeker: Apud Leonardum Strik 1699, URL: https://archive.org/details/GemmaeEtSculpturaeAntiquaeDepictae (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[16] Leonardo Agostini: Le gemme antiche figurate di Leonardo Agostini, 2 vols., Rome: Nella Stamperia del Monaldi 1702, URL: https://archive.org/details/LeGemmeAnticheFigurate_274 (vol. 1) (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[17] Maffei informs his readers about the origin of the plates in the preface; Maffei 1707–09, Parte prima (1707), p. xv, URL: http://polona.pl/item-view/5eb394b4-a676-4858-acba-59089bbd06bc/0/2fe9ebe2-ef6e-451b-aff0-1fa3d84c0925 (last accessed 17 September 2025). For a detailed discussion of the connection between Montfaucon, Maffei, and the engraving series of the Grimani gems attributed to Enea Vico, see the blog post by Timo Strauch: ‘#12: Divided and reunited: Apollo, Daphne and a Bacchanal‘, URL: https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00009759 (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[18] Maffei 1707–09, Parte prima (1707), p. xiv, URL: http://polona.pl/item-view/5eb394b4-a676-4858-acba-59089bbd06bc/0/7f8a4052-754a-41c7-bad0-0220c4d40fbc (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[19] The copper plates revised for Maffei’s edition, originating from the publisher De’ Rossi’s collection, are today preserved in the Calcoteca of the Istituto Centrale per la Grafica in Rome. URL: https://www.calcografica.it/matrici/fondo.php?id=de-rossi&serie=le-gemme-antiche-figurate&pag=1&ordine=3&indirizzo=0 (last accessed 17 September 2025).

[20] 85 of the illustrations copied after ‘Maffei‘ were newly produced for Maffei’s Gemme antiche figurate by Francesco Faraone Aquila; 25 illustrations bearing the attribution ‘Maffei‘ originally derive from the Grimani series attributed to Enea Vico, and two ‘Maffei‘ illustrations are based on plates first published by Pietro Stefanoni.

[21] Vaiani 1998, p. 88; Gennaioli 2017, p. 154. Riccardo Gennaioli has attached to his essay ‘Una passione dinastica. Leopoldo de’ Medici collezionista di oggetti in pietre dure e di gemme‘, a catalogue of the gems formerly owned by Agostini, now identified in the Tesoro dei Granduchi and the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze: see Riccardo Gennaioli: ‘Appendice. Le gemme antiche figurate di Leonardo Agostini Senese‘, in: Valentina Conticelli, Riccardo Gennaioli, Maria Sframeli (eds.): Leopoldo de’ Medici. Principe dei collezionisti (Florence exhibition catalogue 2017–18), Livorno 2017, pp. 165–175.