#10: How did the Palatine come to Naples? The so-called Bagni di Livia as an example of the visualization of the Palatine on behalf of the King of the Two Sicilies

Barbara Sielhorst

Version of the article suitable for citation

on ART-Dok (Heidelberg University Library)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00009826

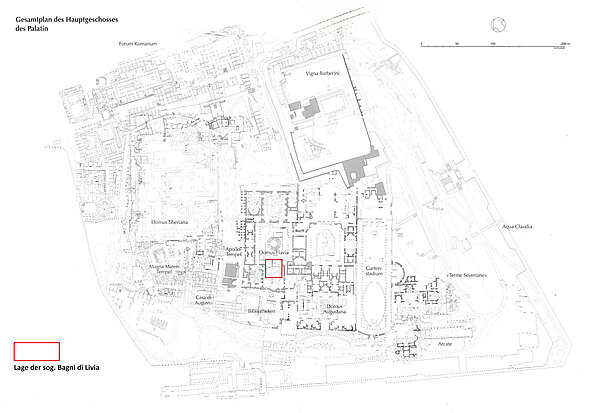

For centuries, the Palatine Hill in Rome has been a place that has aroused the interest of antiquarians and archaeologists and whose exploration is still ongoing today. One of the reasons for this is that the site in the heart of Rome, which covers around 14 football pitches (approx. 10 hectares) and extends over several floors, is too large. Around half of this area belonged the kings of Naples from 1731 to 1861. It comprised the so-called Horti Farnesiani in the west of the Palatine, which were laid out from 1542 above the ancient remains of the Domus Tiberiana and parts of the Domus Flavia. The area was owned by the Farnese family until it became the property of the Bourbons in 1714 through the marriage of Elisabetta Farnese to Philip V of Spain, who from then on were the kings of Naples and Sicily. In the southern tip of this area there were underground rooms with water pipes and rich wall decorations, which were discovered as early as 1721 during excavations commissioned by the Farnese and documented by Francesco Bianchini [1]. The name "Bagni di Livia" quickly became established for this complex, as the house of Livia and, not far away, that of Augustus were thought to be located here (Fig. 1) [2].

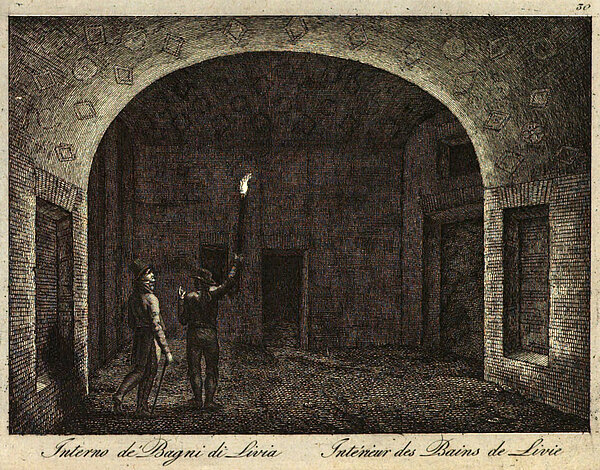

The rich decoration of the rooms, some with gilded wall paintings, made them a popular destination for travellers to Rome in the 18th and first half of the 19th century. They were guided across the Palatine Hill, where they were able to enter the underground rooms of the so-called Bagni di Livia by the light of a torch (Fig. 2).

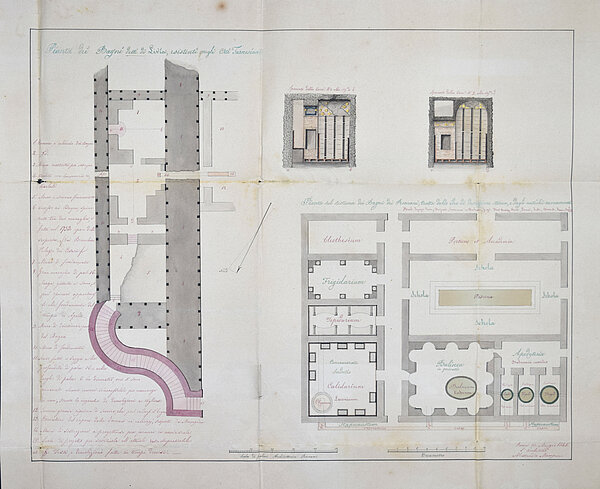

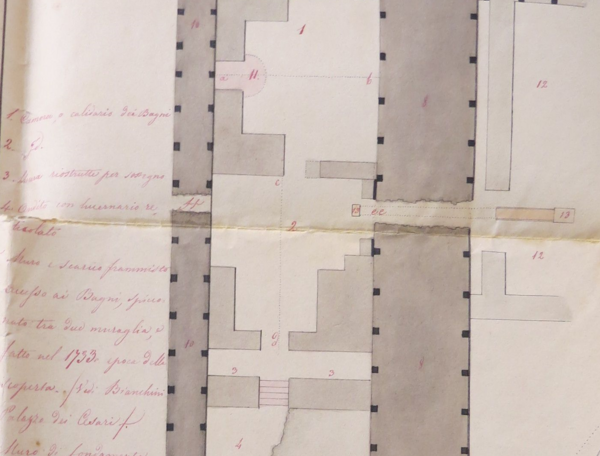

A group of six plans from the period when the Horti Farnesiani were in the possession of the kings of Naples has only recently come to light in the State Archives of Naples [3]. These are four ground plans of the gardens, a sheet with views of the north side of the Domus Tiberiana and a further sheet with ground plans and sections of the so-called Bagni di Livia (Fig. 5). The latter stands out in particular with its juxtaposition of different views and its colorfulness. This sheet will be examined in more detail below against the backdrop of current discourses in visual studies that deal with the generation of plausibility and evidence [4]. The following questions are raised about the illustrations of the Bagni di Livia: What techniques and graphic means were used in their creation? What messages and what knowledge were the images intended to convey? And, in what way is what is depicted made plausible and how do the images generate evidence?

The Horti Farnesiani at a glance

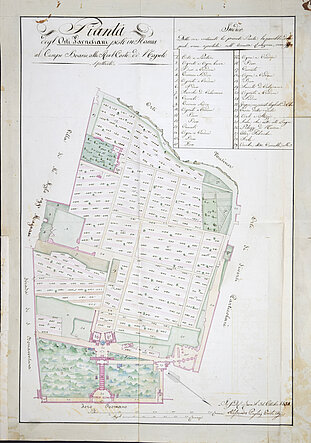

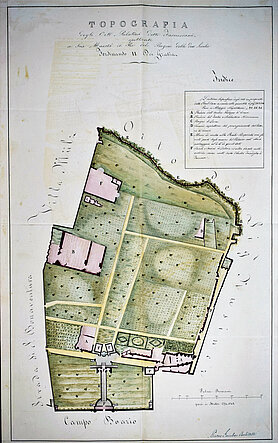

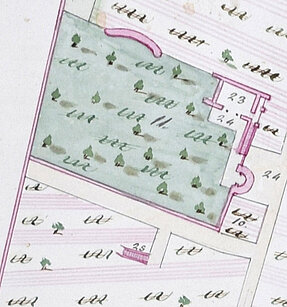

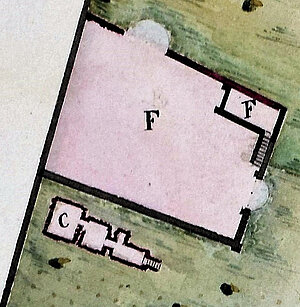

Before that, however, let us take a brief look at two of the ground plans of the Horti Farnesiani, which are also in the Naples State Archives. A comparison of the plans from 1834 and 1855 reveals both interesting similarities and differences in the visualization of the gardens (Figs. 3 and 4).

What the two plans have in common is that they depict the Horti Farnesiani in isolation from their surroundings. The adjacent areas of the gardens are merely named by inscriptions on a neutral background (e.g. in Fig. 3: "Foro Romano" and in Fig. 4: "Campo Boario"), but are not visually characterized any further. Both floor plans also have a title at the top edge, an index at the top right and the name of the draughtsman with the date at the bottom right. In this way, the viewer's gaze is drawn to the gardens in the centre. The scale keys in both drawings should also be mentioned, as they give the viewer an indication of the precision with which the plans were measured and drawn up.

However, it is precisely the differences between the two drawings that shed light on the intended statements and their respective means of plausibility. While the sheet from 1834 depicts the planting of the gardens very schematically by repeating certain symbols, the sheet from 1855 uses green areas with irregularly distributed dark green patches to represent the vegetation. A special feature is the detailed representation of three flowerbeds in the southern half of the plan. The plants there were evidently artfully arranged in the form of two diamonds and a circle in the middle flowerbed.

A closer look at the plan from 1855 titled "Topografia" (Fig. 4) reveals that this drawing shows both the structures visible above and below the surface of the earth. This applies in particular to the underground rooms of the Bagni di Livia (Fig. 4a, "C. Bagni di Livia"). This is not the case in the 1834 plan titled "Pianta" (Fig. 3), which only shows the structures visible on the surface. Instead of the baths themselves, the 1834 map only shows a staircase at this point (Fig. 3a, "25. Scala che mette alli Bagni"), suggesting access to further rooms on a lower level. The caption in the margin makes it clear that this is a staircase leading down to the Bagni di Livia.

The earlier plan (Fig. 3) has a higher degree of standardization in the reproduction of the planting, which is achieved through the use of parallel, thin lines and a more restrained use of colour. In contrast, Gambao's more recent plan (Fig. 4) depicts the horti as a well-tended green oasis, interspersed in a few places with antique structures. The extensive use of the colours green and pink makes the plan appear more like a painting and less like a visual support for the accompanying written documents, which were addressed to the king as the owner of the gardens. The context, in which both plans were used, makes it clear that they were primarily intended to inform the king in Naples about the current state of his possessions in Rome. The means used (perspective, colour, scale key, index, etc.) served not only to convey information about the use of the land but also to create credibility that the king's possessions in Rome were well cared for even without his presence on site.

The so-called Bagni di Livia - fragment and whole

Let us now take a closer look at the underground rooms of the Horti Farnesiani using the sheet on the Bagni di Livia. Their location and furnishings made them a frequently visited place from their discovery in 1721 until the second half of the 19th century. This is documented in a letter from the architect Alessandro Mampieri to the King of Naples, to which the present plan also belongs. The document mentions that the Palatine was visited by "tutti i viagiatori" [5] and that a staircase was therefore needed to allow people to descend to the baths comfortably and safely [6]. For this reason, Mampieri drew up a plan for the construction of a new staircase, which he supplemented with further drawings, so that the sheet contains much more than the staircase installation requested in the letter (Fig. 5).

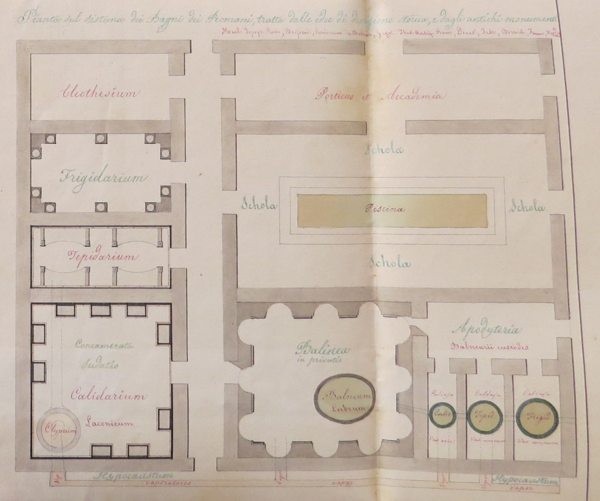

Mampieri's plan consists of a total of four drawings: A ground plan of the Bagni di Livia with the planned construction of a new staircase (left), two sections through the two rooms of the bagni (top right) and the ground plan of a Roman bath (bottom), as it should ideally be imagined. At first glance, it appears that the two ground plans are connected and that the one on the right may represent the entire building and the one on the left only a part of it. However, on closer examination and with the help of the inscriptions, it becomes clear that the plan on the left is a reproduction of the so-called Bagni di Livia excavated on the Palatine Hill, while the one on the right represents an ideal Roman thermal bath complex. This is also confirmed by the title of the drawing on the right in blue ink, which reads: "Pianta sul sistema dei Bagni dei Romani, tratta delle idee di descrizione storica, e dagli antichi monumenti" (Fig. 5a). In the inscription in red ink immediately below, the draughtsman mentions five written sources that he consulted for his reconstruction. These include Bartolomeo Marliani's "Urbis Romae Topographia" from 1550.

Looking at this illustration in conjunction with the ground plan of the Bagni di Livia on the left, one can see that although the architect Mampieri planned the construction of a staircase (plainly visible in pink) as a new entrance to the rooms, it is clear from caption no. 13 that Mampieri had an archaeological interest in his work too. He mentions here that he discovered pipes for the steam from the oven to the caldarium: "13. Conduttori del vapore dalla fornace ai calidarj, scoperti da Mampieri". A comparative examination of the two ground plans with their inscriptions shows that the draughtsman not only wanted to fulfil the king's commission, but also aspired to reconstruct a meaningful whole from the fragmented findings of the underground rooms on the Palatine. To this end, he not only used the pencil in his hand, but apparently also took a closer look around the rooms and even acted as an excavator.

While the ideal ground plan of a Roman thermal bath on the right shows intact walls and smaller structures inside, the plan on the left shows rooms whose shape is not completely known or is irregular (Fig. 5b). The use of different shades of grey visualizes different structural relationships and levels of the brickwork. Walls further up and not belonging to the Bagni di Livia, for example, are shown darker than those of the baths themselves. Numerous numbers in the ground plan are resolved directly next to the drawing with captions explaining the illustration.

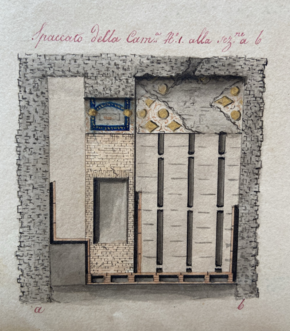

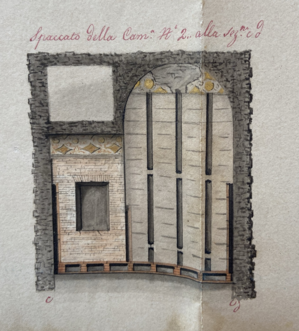

Note the two fine lines (a—b, c—d) that run through the upper and lower spaces. These are markings that indicate which views the sections on the top right of the sheet represent (Figs. 5c and 5d). These are again provided with a heading and the same letters (a—b and c–d resp.), so that the viewer is easily able to connect the images mentally with the correspondent places in the ground plan.

In the sections themselves, the individual walls, the position and shape of the cavities in the walls and floor as well as the wall and ceiling decorations are drawn in detail. In addition to shades of grey and brown, blue and gold were also used in the colour scheme of the sections in order to reflect the colourfulness and the particularly splendid furnishings of the rooms.

Summary

Overall, Mampieri's three types of illustration (record of existing building, section, reconstruction) succeed in creating a visual triangle rich in relationships, so that the drawings complement each other. Starting from the ground plan of the Bagni di Livia, where a survey is first reproduced and described in detail, the view shifts upwards towards the opulent furnishings of the interior, and downwards, so that the bath on the Palatine Hill, which is still visible as a fragment, functions as a pars pro toto for the model of a Roman bath depicted here, which is to be understood in this ground plan as a visualization of the Roman bathing system ("sistema dei Bagni dei Romani") in general. For an experienced observer, this creates a semantic network whose starting point is the Bagni di Livia and which extends from there to both the concrete detail and the abstract principle. With these drawings, the architect Mampieri shows himself to be an archaeologically motivated researcher whose skills and interests go far beyond the commission to build a new staircase. Although the construction task is highlighted in colour in the drawing on the left, a much larger part of the sheet is taken up by the recording of the findings and the (re)construction of a building type to be derived from them.

The depictions are given plausibility not only by the indication of a scale key and the detailed captions (some with measurements), but above all by the power of the model [7] next to the fragment. The images arranged on one sheet create the impression of a relationship in representation between the findings on the Palatine Hill and the complete, ideal Roman bath. The use of similar colours in all the drawings, their richness of detail and the emphasis on dimensional accuracy in the recording ensure that the viewer is willing to accept the reconstructed whole as a logical and correct version of a bath, despite the irreconcilable differences between the objects depicted. By citing the written sources, Mampieri reveals his procedure for obtaining his idea of a complete bath and thus lends it even greater scientific evidence.

With the help of the pictures alone, the draughtsman succeeds in sending several messages at once: 1. The desired new construction of a staircase can be realized by him easily and in an aesthetically satisfying way. 2. The ancient rooms have a technical sophistication and high-quality furnishings. 3. The Bagni di Livia can be classified in the building scheme of Roman baths and help with its reconstruction. All three aspects contribute to the fact that the recipient of the images, the King of the Two Sicilies and owner of the Horti Farnesiani, could feel flattered that he could call such a valuable archaeological complex his own. Last but not least, it was of course Mampieri who put himself in a good light with his drawings; after all, it was he who both planned the construction of the staircase and created and visualized the overarching significance of the baths on the Palatine in his network of images.

Despite or because of the obvious 'gaps’ between the findings and the model, the images activate the imagination of the viewer, who is thus enabled to envision something that was not present in reality. A procedure that has been known in architectural theory since Vitruvius and appears here in a new form. The juxtaposition of findings and reconstruction, as practiced by the Grand Prix winners of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, among others, is typical for the period in which the present sheet was created and for the 19th century as a whole [8]. As the comments on this example show, it is a worthwhile endeavour to further research the history of visualization of the Palatine and in particular the so-called Bagni di Livia in order to gain deeper insights into the role of images and in particular of reconstructions and models in the archaeological knowledge process [9].

[1] F. Bianchini, Del Palazzo de’ Cesari. Opera Postuma (Verona 1738), 34.74, https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.6029; C. Hülsen, Untersuchungen zur Topographie des Palatins, Römische Mitteilungen 1895, 255.258 (ground plan).

[2] Today we know that the rooms were a nymphaeum with a triclinium in front of it, which belonged to the Domus Transitoria of Nero. H. Manderscheid, Was nach den „ruchlosen Räubereien“ übrigblieb – zu Gestalt und Funktion der sogenannten Bagni di Livia in der Domus Transitoria, in: A. Hoffmann – U. Wulf (eds.), Die Kaiserpaläste auf dem Palatin in Rom. Das Zentrum der römischen Welt und seine Bauten (Mainz 2004) 75–85.

[3] V. Santoro – B. Sielhorst – L. Terzi, I Borbone sul Palatino. Documenti inediti sugli Orti Farnesiani dal 1731 al 1861, Römische Mitteilungen 128, 2022, § 1–136, https://doi.org/10.34780/076c-7aj6.

[4] For examples of current discussions in the German-speaking humanities on the generation of plausibility and evidence: A. Flüchter – B. Förster – B. Hochkirchen – S. Schwandt (eds.), Plausibilisierung und Evidenz. Dynamiken und Praktiken von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart (Bielefeld 2024) as well as the research of the Kolleg-Forschergruppe „Bildevidenz. Geschichte und Ästhetik“, active at the FU Berlin from 2011 to 2024: http://bildevidenz.de/ (25.06.2024).

[5] V. Santoro – B. Sielhorst – L. Terzi, I Borbone sul Palatino. Documenti inediti sugli Orti Farnesiani dal 1731 al 1861, RM 128, 2022, § 1–136, PDF Appendice, document 6 Maggiordomina, III inv., b. 2055, f. 253 (PDF Sp. 39), https://doi.org/10.34780/076c-7aj6.

[6] V. Santoro – B. Sielhorst – L. Terzi, I Borbone sul Palatino. Documenti inediti sugli Orti Farnesiani dal 1731 al 1861, RM 128, 2022, § 1–136, PDF Appendice, document 6 Maggiordomina, III inv., b. 2055, f. 253 (PDF p. 34), https://doi.org/10.34780/076c-7aj6: ”2° Il progetto per la costruzione di una scala a potervi discendere più agiatamente e senza pericolo”.

[7] On the theoretical discourse and the intrinsic value of models, see R. Wendler, Das Modell zwischen Kunst und Wissenschaft (Munich 2013) and the review by C. Beese in: Sehepunkte 15 (2015), no. 10 [15.10.2015], https://www.sehepunkte.de/2015/10/25927.html (24.06.2024).

[8] As an example, the studies by Jaques-Jean Clerget from 1838 and Jean-Louis Pascal from 1872 should be mentioned here, who, according to the statutes of the scholarship, had to produce both a drawing of the actual state of an ancient building at the time and a reconstruction drawing. See Clerget's drawings of the House of Augustus in the collection of the Académie des Beaux-Arts de Paris, Env 31-06, Env 31-07; see Pascal's drawings of the garden stadium on the Palatine Hill in the collection of the Académie des Beaux-Arts de Paris, inv. no. Env 61-09, Env 61-11.

[9] This is the aim of the DFG project carried out by the author "From the hand drawing to the digital model. The Palatine in Rome as a case study for knowledge production in archaeology" (project no. 524436111) at the Institute for Archaeological Sciences at the Ruhr University Bochum. Project page on the RUB website: https://www.archwiss.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/aw/forschung/palatin.html.en (24.06.2024). Project page on the geoinformation system "PalatinGIS", which is being developed as part of the project: https://arachne.dainst.org/project/palatinGIS?lang=en (24.06.2024).