#12: Divided and reunited: Apollo, Daphne and a Bacchanal

Timo Strauch

Version of the article suitable for citation

on ART-Dok (Heidelberg University Library)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00009828

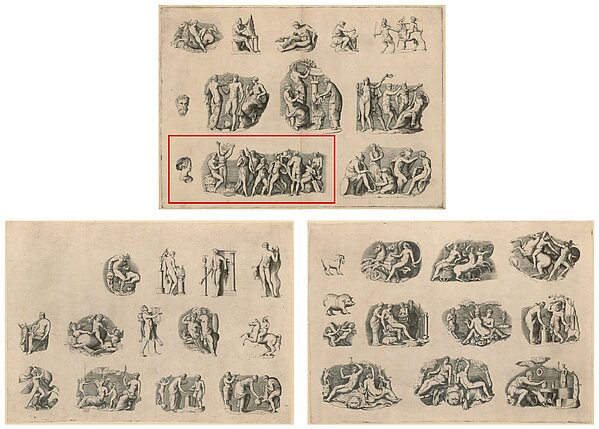

Once again, the systematic indexing of the illustrations in Bernard de Montfaucon's ‘L'antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures’ (1719) provides an opportunity for the Antiquitatum Thesaurus to trace the reception of a (non-)antique artefact in the visual sources of the 16th to 18th centuries. As in blog posts #3 and #7, the triggering moment is that Montfaucon shows two images where only one object is actually meant. In this case, however, the reason for this is different from that of the chicken cage or the block statue, so that there is also an opportunity to present new aspects of the work of the Thesaurus and central mechanisms of the visual transmission of antiquity in the early modern period. [1]

From Montfaucon to Lafreri

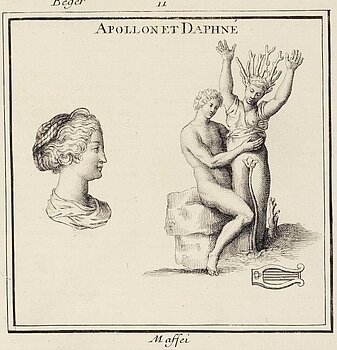

In the first two volumes of the ‘Antiquité’, Montfaucon deals with the gods of the Greeks and Romans. In two chapters of the third book in vol. 1.1, 38 images on seven plates illustrate the god Apollo and the most important episodes of his appearance in classical mythology. On pl. 52, in addition to ten coin images, the illustration in fig. 11 is framed separately in a square and labelled ‘Apollon et Daphné’ (fig. 1; ThesaurusID 23919994).

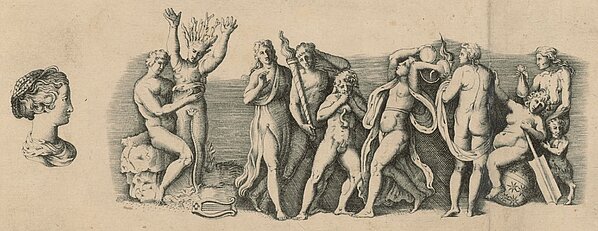

On the left is the portrait of a young woman in profile, turned to the right. Her gaze falls on Apollo sitting on a rock, holding Daphne, who is standing between his legs. She has raised both arms in panic, while her transformation into a laurel tree has already begun with her feet stuck in the ground and her hair turning into branches. The source of the illustration is given as ‘Maffei’. In the accompanying text, Montfaucon briefly repeats the well-known story, as described by all mythographers, and identifies the profile portrait with Daphne in her natural appearance: ‘La tête qu'on voit à côté, est celle de Daphné dans son naturel.’ He then refers to St John Chrysostom, who describes the transformation of Daphne into a laurel tree as the founding myth of the Antioch suburb of the same name. Montfaucon says nothing about the depicted object. [2]

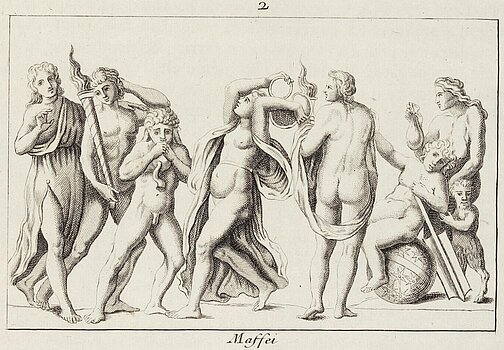

The same applies to his description of fig. 2 on pl. 143 in vol. 1.2 of the ‘Antiquité’ entitled ‘Bacchanales’, which is assigned to the chapter in which Montfaucon deals with the childhood of Bacchus, among other things (fig. 2; ThesaurusID 2392026).

In the rectangular framed scene, he recognises the infant Bacchus in the figure sitting on a globe on the right and describes the other personnel, who are equipped with torches, musical instruments or a bag, as his entourage, apparently without being entirely convinced of this identification himself: ‘Tout ceci est mysterieux.’ [3] His source here is again ‘Maffei’.

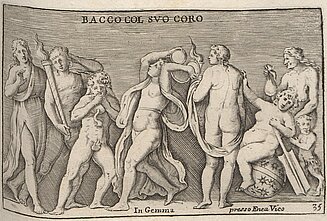

The two models are quickly found in the four-volume ‘Gemme antiche figurate’ by Paolo Alessandro Maffei (1707–09). On pl. 44 in vol. 2 appears ‘Dafne convertita in alloro’, classified as ‘in Gemma’, and on pl. 35 in vol. 3 we see ‘Bacco col suo coro’, also classified as ‘in Gemma’. Maffei provides additional references directly next to the illustrations: ‘presso lo Stefanonio’ for Apollo and Daphne and ‘presso Enea Vico’ for the Bacchanal (figs. 3 and 4; ThesaurusID 23925598 and ThesaurusID 23926319).

In the introduction to his book on gems published by De' Rossi, Maffei clearly states that the majority of the more than 400 illustrations were taken from older publications, namely from the “Gemme antiche figurate” by Leonardo Agostini and from unspecified publications by Enea Vico and Pietro Stefanoni. [4] Unlike Montfaucon, Maffei did not need to copy the models and have them engraved anew, because he had direct access to the copper plates of his predecessors in the De' Rossi Calcografia. However, Maffei shuffled, reorganised and redistributed the material within his four volumes and in the course of this, Maffei also had the inscriptions on the plates revised. [5] In doing so, he occasionally made mistakes, as in the case of Apollo and Daphne: this scene, like the Bacchanal, should also have been labelled ‘presso Enea Vico’.

Because prior to Maffei, both plates were part of the series published by Giovanni Domenico de' Rossi (1619–1653) under the title “Ex gemmis et cameis antiquorum aliquot monumenta ab Aenea Vico Parmen. incis.” and dedicated to the natural scientist Domenico Panarolo (1587–1657). The title page of the series bears no date, but it is usually dated ‘around 1650’. In addition to the title page, it comprises 33 numbered plates, the illustrations of which are labelled with Latin titles and Latin quotations without any indication of their sources (ThesaurusID 23938420).

The female portrait with Apollo and Daphne is shown here in pl. 16 and is entitled ‘Daphne in Laurum conversa’. The caption reads: ‘Perpetuo viridem servat Phoebęa colourem Daphne’ (fig. 5; ThesaurusID 23938436). The Bacchanal can be found on pl. 12 with the simple title ‘Bacchus’, accompanied by the caption: ‘Ecce Mimallonides sparsis in terga capillis. Ecce leves Satyri’ (fig. 6; ThesaurusID 23938432). With regard to the titles, Maffei thus primarily provided a translation and clarification. Retaining the lyrical quotations on the plates of the Vico De' Rossi series, on the other hand, would have disturbed the uniformity of his publication, as Agostini's and Stefanoni's engravings had nothing comparable to offer.

Only in the case of the Bacchanal is it possible to determine the origin of the two quotations without too much effort. The unusual vocabulary quickly leads to Ovid's ‘Ars amatoria’: ‘Ecce Mimallonides sparsis in terga capillis. Ecce leves satyri, praevia turba dei.’ (lib. I. 541–542). In the case of Apollo and Daphne, a Google search initially yields only one suitable source, namely on p. 236 of the ‘Epithetorum Ioannis Ravissi Textoris Nivernensis Opus Absolutissimum’, published in Douai in 1607. [6] This is a posthumous edition of a work by the French humanist and rhetorician Jean Tixier (Johannes Ravisius, 1480?–1524), which first appeared in 1524. The epithet ‘Phoebęa’ can already be found there on fol. 125 v under the bynames of Daphne, which is attested with the quotation repeated in Vico-De' Rossi, whose source is given as a certain Palladius Soranus. [7] This reference in turn leads to an epigram by Domicus Palladius (1460?–1533), which probably first appeared in print in his ‘Epigrammata’ of 1498: [8]

„Ad Bartolomeum venerabilem sacerdotem.

Perpetuo viridem servat phoebea colorem

Daphne: nec longo vincitur illa die.

Sic utriusque tibi laudes & gloria linguae:

Famaque sub celebri nomine semper erit.

Sic quoque pro meritis vero devinctus amore

Obsequar optaris Bartolomee tuis.“

The exact source that Giovanni Domenico de' Rossi used around 1650 for his selection of the motto for the Apollo and Daphne engraving may be clarified once the origin of the quotations on the other 32 engravings in the series has also been determined. In our context, however, this question does not play a decisive role, as the origin of the copper plates can also be traced independently of this.

In fact, the series was first published around 30 years earlier, albeit again in a different state and with a different title. The French-born Philippe Thomassin (1562–1622) turns out to be the actual creator of the series of 33 sheets plus title page, whose inscription here bears the title ‘Ex antiquis cameorum et gemmae delineata, liber secundus, et ab Enea Vico Parmen. incis.’ [9] The work is dedicated to the renowned antiquarian and collector Francesco Angeloni (1587–1652). In contrast to De‘ Rossi, the engravings here are still without any meaningful labelling; only the consecutive numbering from 1 (title page) to 34 is already the same as that retained unchanged by De’ Rossi (ThesaurusID 23940128). Accordingly, Apollo and Daphne can also be found here on pl. 16 and the Bacchanal on pl. 12 (figs. 7 and 8; ThesaurusID 23940475 and ThesaurusID 23940471).

However, we have still not reached the origin of the illustrations. The reference to Enea Vico as the author of the engravings, which has been handed down to Maffei, and the designation of the origin of the motifs as coming from cut stones – gems and cameos – refers to a series of three engravings from the publishing house of Antonio Lafreri (1512–1577) in Rome, which in turn are known in at least three states. They are listed in the so-called ‘Lafreri Index’, a catalogue of the publisher's available publications, which can be dated to the period between 1575 and 1577. [10] However, it is not clear from the index since when they were offered and who the engraver was.

In their first state, they are without any inscriptions (fig. 9; ThesaurusID 23948511, ThesaurusID 23948525, ThesaurusID 23948527). In the second state, all three have the address ‘Romae Claudij Duchetti sequani q. Antonij Lafreri nepos formis’, which indicates that the plates came into the possession of Claudio Duchetti when Lafreri's estate was divided among his nephews. Giovanni Orlandi acquired the plates from the Duchetti's estate in 1602 and labelled them accordingly: ‘Ioannes Orlandi formis romae 1602’. [11] There is a fourth state of two of the three engravings, with the misleading addition ‘Ex antiquis marmoribus’. [12] No copy of the fourth state of the sheet with the Apollo and Daphne Bacchanal has yet been identified.

On the other hand, the designation ‘Apollo and Daphne Bacchanal’, which we have just introduced, indicates what is most significant in our context: the original state of the two scenes, which survived separately until Montfaucon, is actually a common one, while the female portrait head in profile represents a separate, as yet unidentified model (fig. 10; ThesaurusID 23948523 and ThesaurusID 23948522).

In his ‘incisive’ treatment of the former Lafreri plates, Philippe Thomassin evidently considered it impractical to treat the portrait head, which is rather small in relation to most of the other motifs, as a separate plate and therefore decided to separate the Apollo and Daphne scene from the bacchanal in order to ‘merge’ it with the portrait instead. Thomassin combined what were originally two separate motifs into a new image in four other cases, but only here did he divide a motif that belonged together. Another of Thomassin's contributions to the design of ‘his’ series was the addition of the originally irregularly delimited background hatching, so that rectangular framed images were created for each motif. Finally, he also departed from the order of the Lafreri sheets when numbering the newly created panels, i.e. the motifs were now arranged in a new sequence, whereby the decisive criteria for the order are not readily recognisable neither on the three individual sheets nor in the series.

The three Lafreri sheets with a total of 37 motifs have long been associated with the Grimani collection of gems, the reconstruction of which has been the work of Edith Lemburg-Ruppelt and, after her, Oleg Neverov, Irene Favaretto, Marcella di Paolo and Denise La Monica. [13] So far, 26 of the 37 gems depicted in the engravings have been identified with pieces that are still preserved today or have been lost, while the other 11 have not yet been found.

From Venice to Paris

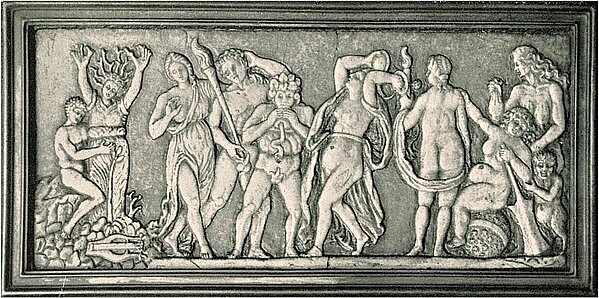

Our piece, the Apollo and Daphne Bacchanal, is a ‘lost’ one, as it appears to have been recorded for the last time in 1929. At that time, Ernst Kris illustrated it in his ‘Meister und Meisterwerke der Steinschneidekunst’ and located it in the collection of Carle Dreyfus (1875–1952) in Paris (fig. 11). [14]

Before that, in 1908, Gaston Migeon had mentioned and also illustrated the stone in his detailed description of the collection of Carle's father, Gustave Dreyfus, in the chapter on small bronzes and reliefs, basically as a throw-in, but nevertheless with high esteem. Migeon writes:

„D’une charmante composition, d’un rythme savant et cadencé, est la jolie plaque en pierre dure ou le mythe de Daphné est interprété en léger relief blanc sur un fond gris, et dans maintes estampes des Bacchanales de Mantegna se retrouverait encore l’heureuse disposition en frise des Corybantes de cette délicieuse oeuvre ferraraise.” [15]

According to this, the object is a pietra dura cameo with white figures on a grey background, which Migeon associates with thematically related engravings by Andrea Mantegna and classifies as ‘Ferrarese’. We learn nothing about the dimensions of the object.

Ernst Kris classifies the piece as ‘’Northern Italian, XVIth century‘’. He depicts it together with the engraving of the Bacchanal in a state that must have been created after Maffei's ‘Gemme antiche figurate’, in which Kris recognised the obvious relationship. However, he evidently did not have Maffei's plate with Apollo and Daphne and the female portrait at hand and therefore assumes that the relief was ‘freely based on an engraving [...] extended by the group of Daphne.’ [16]

The collection of Gustave Dreyfus (1837–1914) has been thoroughly analysed by Alice Silvia Legé. She also discusses the pietra dura relief, but likewise assigns it only the role of a remarkable unicum, which only receives a detailed footnote in addition to an illustration. [17] In her subsequent description of the dispersal of the Dreyfus Collection around 1930, she concentrates on the famous bronze plaques and medals, which were sold en bloc to America and eventually ended up in the National Gallery of Art in Washington via the Kress Collection. Whether the collection items of other media also ended up in America via the Duveen Brothers or were dispersed in Europe without further documentation has not yet been clarified. [18]

Instead, we know of sources at the other end of the relief's chronology. It is first mentioned in an inventory ordered by the Patriarch of Aquilea and Bishop Marino Grimani (1488/89?–1546) on the occasion of his move from Venice to Rome in 1528. It is listed as ‘Storia di Dafne in Cameo tenero molte figure ligato in ferro’. [19] Alice Silvia Legé has pointed out that in the longer list of the various tablets with cameos, four to six stones are always mentioned per tablet; only tablet no. 33 contained the ‘Storia di Daphne’ alone – apparently an indication of the extraordinary size of the object.

The piece appears once again in a description of the famous studiolo Grimani, an elaborately designed ebony cabinet decorated with numerous bronze figures, reliefs and cut stones. The description is part of an inventory of the donation made to the Serenissima in 1593 by the Patriarch of Aquilea Giovanni Grimani (1506-1593). According to this, the Apollo and Daphne bacchanal was placed in a crowning position of the studiolo: ‘Un cameo grande fuori del niccio nel frontispizio co’ X figure, fra donne huomini et fauni.’ [20] The size of the piece is explicitly emphasised here. Two detailed descriptions of the studiolo from the 18th century (1749 and 18 October 1793) still refer to the relief as part of the whole, before it is no longer mentioned in a further document on the studiolo dated 13 November 1793. [21]

Before we return to the graphic reproductions, we will briefly summarise what we know about the relief (cf. ThesaurusID 23954474): It is a raised carved hard stone with white figures on a grey background, the size of which apparently exceeded that of the other gems in the Grimani Collection. It is not an antique work of art, but probably a product of the late 15th or early 16th century. The actual origin of the relief, its stylistic classification, the interpretation of its content and the exploration of the reception of antiquity expressed in its motifs cannot be pursued further in this contribution. It was in the possession of the Grimani family in Venice from the 1520s at the latest. As part of the studiolo Grimani created in Venice in the second half of the 16th century, it remained in the city before its traces were lost in 1793. [22] Then, in the early 20th century, it was in the Dreyfus Collection in Paris, where it presumably came onto the art market around 1930 and disappeared until today.

From Battista to Giacomo

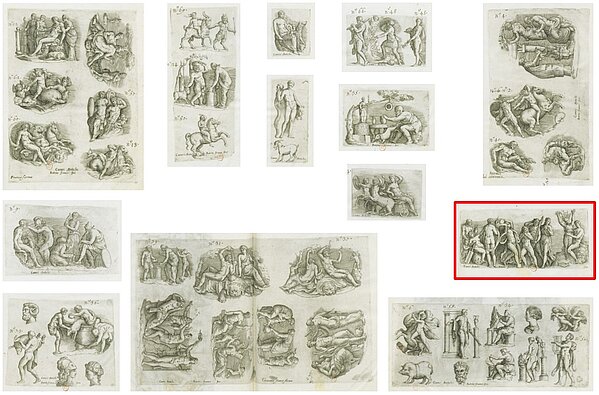

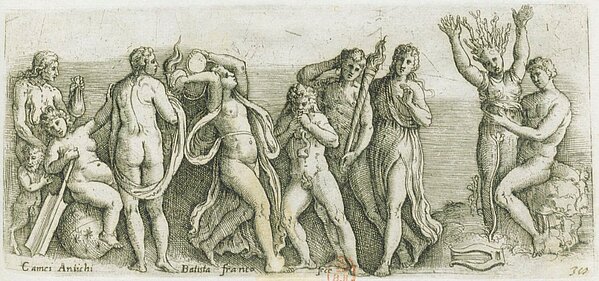

Between the two written testimonies of 1528 and 1593, the origin of the visual documentation of the pietra dura relief still needs to be added. It is very likely that the three Lafreri engravings were not the first translation of gems from the Grimani collection into prints. Rather, research attributes the primacy to another series: Battista Franco (before 1510–1561) is responsible for a group of 13 sheets with a total of 45 etchings after cut stones, among which all 37 motifs of the Lafreri series can be found. In addition to the larger number, the laterally reversed orientation of the etchings is particularly striking. Several states of this series have also survived: the first without an inscription, the second labelled ‘[Giacomo] Franco forma’ and the third additionally labelled ‘Camei antichi’ and/or ‘Battista Franco fece’ (Abb. 12). [23]

The Apollo and Daphne Bacchanal was given its own plate by Franco and could therefore be printed and sold separately (fig. 13; cf. ThesaurusID 23954833; state from 1611). It is similar in size to Enea Vico's supposed copy and the comparison of the two prints also shows a marked similarity with regard to design. Only the faces reflect the individual styles of the two artists.

Franco's etchings are possibly connected with the repurchase by Giovanni Grimani in 1551 of the collection of Marino Grimani, who had died in 1546 heavily in debt. [24] Franco also worked as a painter on behalf of the family in Venice in the 1550s and was therefore probably the first candidate for a commission to publish a selection of the returned gems. Whether Enea Vico copied Franco's finished etchings for the publisher Lafreri in Rome or engraved them from the same preparatory drawings as Franco is an open question, as is the reason for the reversed (Franco) or correct orientation (Vico) of the images compared to the cut stones and the reason for the reduced number of motifs within the Lafreri series. [25]

From Lafreri to Hohenburg and Pignoria

Finally, let us take another look at the Apollo and Daphne Bacchanal. Away from the engraving series, but dependent on them as models, it found its way almost simultaneously into two other early modern pictorial compendia of very different design.

For one, in the ‘Thesaurus hieroglyphicorum’ by Hans Georg Herwart von Hohenburg (1553–1622), which was probably published in Munich around 1610. Here it appears as fig. 44 on a plate together with a copy after a two-part engraving depicting an allegory of virtue and vice attributed to the school of Andrea Mantegna (fig. 14; ThesaurusID 1684751 and ThesaurusID 1684750). [26]

With an impressive sense for similarities in motif and style, Herwart von Hohenburg here brings together two images whose roots are probably to be found in the same period and the same intellectual environment. How exactly he interpreted the content of the two ‘hieroglyphic pictures’ for him – each figure is labelled with a letter to which the missing text would presumably have referred – unfortunately remains hidden. As Herwart von Hohenburg copied a number of other sheets from the Lafreri publishing house, it is reasonable to assume that he used one of the three engravings from Rome for his very precise copy and not a (laterally reversed) etching by Battista Franco from Venice. [27]

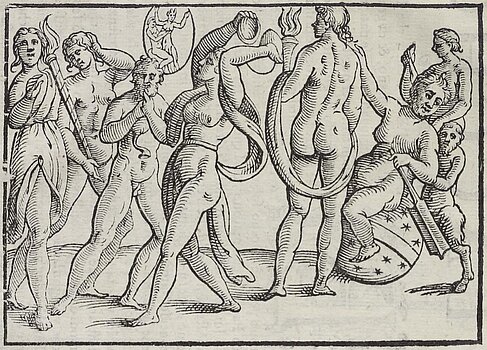

The last example (for the time being?) of a transfer of the same subject into a new context is provided by Lorenzo Pignoria (1571–1631) in his expanded edition of Vincenzo Cartari's ‘Le imagini de i dei degli antichi’, which first appeared in 1615. [28] On p. 367, a woodcut with the well-known motif introduces the chapter on Bacchus (fig. 15; ThesaurusID 23954485).

In contrast to Herwart von Hohenburg's precise copy, Pignoria takes a completely different approach to the model: Analogous to the physical cut through the copper plate that Philippe Thomassin will make a little later, Pignoria separates the Bacchanal from Apollo and Daphne. While the eight Bacchantic figures can move for the first time in a pictorial space with a certain depth, Apollo and Daphne are displaced on a drastically reduced scale into the oval framing of a separate image inserted at the upper edge of the scene. Pignoria evidently wanted to distract his readers' attention from this motif, which in fact does not belong to the Bacchic theme and its iconography. However, in order not to omit it completely, he added it – in the form of a gem of all things – just as he repeatedly emphasises the historically based derivation of the ‘Imagini de i dei degli antichi’ on numerous other plates in the same book, usually with authentic images of gems or coins. The accompanying text deals exclusively with Bacchus and the effects of the wine he invented. Without explicit information from the author, it remains unclear whether Pignoria was aware of the origin of his model in this case. For chronological reasons, it seems reasonable to assume that here again a Lafreri engraving (of the same orientation) was used as a model.

In conclusion

The Bacchanal with Apollo and Daphne is another vivid example of the complexity of antiquarian imagery in the early modern period. The network of copies prevalent in the corpus of sources so far catalogued for the Antiquitatum Thesaurus is supplemented here – and in the Lafreri series after the Grimani gems as a whole – by the reuse of the same printing plates in up to six different states over a period of 150 years, further complicated by the cutting up and subsequent recombination of motifs. The original ‘silent’ nature of the images, in the sense of a lack of identifying labelling, soon led to the classification of the models as ‘antique’ cameos, which is applied to all objects in the engraving series regardless of their actual age. However, it also encourages a synaesthetic charging through poetic commentaries, which are selected with scholarly enthusiasm from the humanistic treasure trove of quotations, only to be erased again in the next state and replaced by (at times false) indications of origin. It remains the aim of the Antiquitatum Thesaurus to be an adequate and useful reference work for these items as well.

[1] I would like to thank Luisa Siefert and Emily Grabo for their support in compiling and organising the extensive material that was necessary for the ongoing data entry and its distillation into this blog post.

[2] Montfaucon 1719 (L'antiquité, 1st ed.), vol. 1.1, p. 105.

[3] Montfaucon 1719 (L'antiquité, 1st ed.), vol. 1.2, p. 232.

[4] Maffei 1707–09 (Gemme antiche figurate), vol. 1 (1707), pp. xiij–xv.

[5] Anna Grelle Iusco: Note all’Indice del 1735 e alle tavole sinnotiche, in: Indice delle stampe intagliate in rame, a bulino, e in acqua forte, esistenti nella stamparia di Lorenzo Filippo de’ Rossi […]. Contributo alla storia di una Stamperia romana, ed. by Anna Grelle Iusco, Rome 1996, pp. 373–511, here p. 388, refering to ‚p. 19 c. 2‘.

[6] https://mateo.uni-mannheim.de/camenaref/tixier/tixier1/jpg/s236.html.

[7] https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k858868m/f282.item.

[8] https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/view/bsb00058583?page=12.

[9] Only in this version did the engravings find their way into Adam von Bartsch's catalogue. Adam von Bartsch: Le peintre graveur, 21 vols., Vienna 1802–1821, vol. 15 (1813), pp. 318–324, nos. 100–133; thereafter The illustrated Bartsch, vol. 30: Italian masters of the sixteenth century. Enea Vico, ed. by John Spike, New York 1985, pp. 85–101, nos. 100–133.

[10] „Tre tavole de diversi intagli de Camelli fragmenti dove si vedono di molte sorte de sacrifitij et altre cose varie“; quoted after Birte Rubach: Ant. Lafreri formis Romae. Der Verleger Antonio Lafreri und seine Druckgraphikproduktion, Berlin 2016, p. 346. For the dating of the 'Index' ibd. p. 77.

[11] For a list of copies of each state, see Rubach 2016, p. 346. The exact whereabouts of the plates from Lafreri's publishing house with various other engravers and publishers can be traced precisely on the basis of archival sources, which Valeria Pagani has published in several essays.

[12] This state does not appear to have been recorded in the literature to date. The two copies are Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Inv.-Nr. RP-P-2001-25 and RP-P-2001-26.

[13] Edith Lemburg-Ruppelt: Die berühmte Gemma Mantovana und die Antikensammlung Grimani in Venedig, in: Xenia. Semestrale di Antichità 1 (1981), pp. 85–108; Oleg Neverov: La serie dei ‚Cammei e gemme antichi‘ di Enea Vico e i suoi modelli, in: Prospettiva 37 (1984), pp. 22–32; Edith Lemburg-Ruppelt: Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Cameen-Sammlung Grimani. Gemeinsamkeiten mit dem Tesoro Lorenzos de’ Medici, in: Rivista di archeologia 26 (2002), pp. 86–114; Irene Favaretto, Marcella de Paoli: I ‘Cammei di diverse sorte’ di Giovanni Grimani, Patriarca di Aquilea. Intricate vicende di una collezione di gemme nella Venezia del XVI secolo, in: Aqilea e la glittica di età ellenistica e romana, ed. by Gemma Sena Chiesa, Elisabetta Gagenti, Triest 2009, pp. 261–280; Denise La Monica: Battista Franco, Enea Vico e le stampe dei cammei Grimani, in: Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia, Series 5, vol. 6 (2014), pp. 781–810, 887–903. Cf. also Marrilyn Perry: Wealth, art, and display. The Grimani cameos in Renaissance Venice, in: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 56 (1993), pp. 268–273; Marcella de Paoli: Ancora sulla fortuna delle gemme Grimani. Un paradigma efficace, in: Engramma 150 (2017), pp. 469–488; https://www.engramma.it/eOS/index.php?id_articolo=3253.

[14] Ernst Kris: Meister und Meisterwerke der Steinschneidekunst, 2 vols., Vienna 1929, vol. 1, p. 30 and p. 154, no. 50/15 and 51/15, vol. 2, pl. 15.

[15] Gaston Migeon: La Collection de M. Gustave Dreyfus (Peinture, Bronze), in: Les Arts. Revue Mensuelle des Musées, Collections, Expositions 7 (1908), no. 73 (Janvier 1908), p. 32, fig. on p. 30.

[16] Kris 1929, vol. 1, p. 154, no. 50/15.

[17] Alice Silvia Legé: Gustave Dreyfus. Collectionneur et mécène dans le Paris de la Belle Époque, Milan 2019, p. 86 with note 306, p. 138 with fig. 60.

[18] Our relief does not appear in the Hôtel Drouot sales catalogue of 23–24 October 1930, in which various Dreyfus objects are listed without mention of the collector's name; https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bd6t5381941b; cf. Legé 2019, pp. 103–104, with notes 380–382.

[19] Pio Paschini: Le Collezioni archeologiche dei Prelati Grimani del Cinquecento, in: Atti della Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia, Series III, Rendiconti V (1926–27), pp. 149–190, here p. 180; cf. Lemburg-Ruppelt 1981, p. 104.

[20] Cesarae Augusto Levi: Le collezioni veneziane d'arte e d'antichità dal secolo XIV. ai nostri giorni, 2 vols., Venice 1900, vol. 2: Documenti, p. 8 (https://archive.org/details/lecollezionivene1to2levi/page/8/mode/1up), cf. Lemburg-Ruppelt 1981, p. 104.

[21] 1749: „Cammeo in tavola bislonga, grande, rappresentante Apollo e Dafne et altre figure al numero di dieci“; 18 October 1793: „Un bassorilievo di pietra tenera istoriato di sopra ch’è nel mezzo“; quoted after Anna Maria Massinelli: Lo studiolo „nobilissimo“ del patriarca Giovanni Grimani, in: Congresso internazionale Venezia e l’archeologia. Un importante capitolo nella storia del gusto dell’antico nella cultura artistica veneziana, ed. by Irene Favaretto, Gustavo Traversari, Rome 1990 (Supplementi alla Rivista di Archeologia, 7), pp. 41–49, here p. 43, 44.

[22] Lemburg-Ruppelt assumes that the Grimani gems, which were not part of the studiolo, were transferred to the Nani Collection; from there, the dispersal of this far more extensive sub-collection began at the end of the 17th century; Lemburg-Ruppelt 1981, pp. 96–99.

[23] Bartsch 1802–1821, vol. 16 (1818), pp. 146–154, nos. 81–93. The third state appeared in 1611 in the book ‘Della nobiltà del disegno diviso in due libri’ published by Battista Franco's son Giacomo; ThesaurusID 23954722. The second state has so far only been documented for two of the 13 leaves.

[24] Lemburg-Ruppelt 1981, p. 92; Franco also worked as a painter for the family in Venice.

[25] Lemburg-Ruppelt 1981, pp. 92–93. Denise La Monica proposes an alternative hypothesis by dating Battista Franco's original drawings to the period before Marino Grimani's death, as motifs based on the gems can already be found in Franco's majolica designs from the 1540s. Enea Vico may have copied Franco's drawings as early as the 1540s, but only published them as engravings with Lafreri after the publication of Franco's etchings; see La Monica 2014, passim and diagram on p. 810. The 22 pen and ink drawings that came onto the art market in 2015 and have been in private ownership since then may also be important in answering the questions surrounding the creation of the two series. They date from the 16th century and show 20 motifs that appear in both printed series and one motif that only appears in Franco's, in the same orientation as the Lafreri engravings and the original gems. One motif from the series of drawings does not appear in either of the two printed series. I owe the reference to the drawings to Pawel Gołyźniak.

[26] Arthur M. Hind: Early Italian engraving. A critical catalogue with complete reproduction of all the prints described, 7 vols., London 1938–1948, vol. 5 (1948), pp. 27–29, no. 22; Mark J. Zucker: Early Italian masters (=The illustrated Bartsch, vol. 25: Commentary), New York 1984, pp. 126–127, nos. .026, .027 and .026-.027 C1.

[27] For the upper half of the engraving from the Mantegna school, a drawing is preserved in the British Museum (inv. Pp,1.23), which is regarded as Mantegna's original design; cf. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_Pp-1-23 with the catalogue entry from Popham, Pouncey 1950. Hind, Popham and Pouncey as well as Zucker know the reduced copy of the engraving with 21 letters, but its origin from von Hohenburg's ‘Thesaurus hieroglyphicorum’ has apparently been overlooked until now. Popham and Pouncey also cite the etching of the Apollo and Daphne Bacchanal by Battista Franco with the inscription ‘Camei Antichi’ and assume that its model could be an ‘imitation’ of the antique, going to back to Mantegna. The link to the Grimani-Dreyfus relief had not yet been recognised at this time.

[28] In the ‘Seconda novissima editione’, published by Pignoria in 1626, the same woodcut is printed a second time (p. 339); cf. ThesaurusID 23954449.

![5 Vico, De Rossi [c. 1650] (Ex gemmis et cameis), pl. 16 (Photo: SUB Göttingen)](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/6/csm_blog12_abb_05_d2d79ae429.jpg)

![7 Vico, De Rossi [c. 1650] (Ex gemmis et cameis), pl. 12 (Photo: SUB Göttingen)](/fileadmin/_processed_/1/b/csm_blog12_abb_06_6aaf4b4285.jpg)

![7 Vico, Thomassin [c. 1620] (Ex antiquis cameorum), pl. 16 (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/9/csm_blog12_abb_07_b698ed9c28.jpg)

![8 Vico, Thomassin [c. 1620] (Ex antiquis cameorum), pl. 12 (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/2/csm_blog12_abb_08_25194b7331.jpg)

![14 Herwart von Hohenburg [c. 1610] (Thesaurus hieroglyphicorum), figs. 43 and 44 (Photo: SUB Göttingen)](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/b/csm_blog12_abb_14_d332a5e762.jpg)