#11: πάντα ῥεῖ: "Everything flows" – The Nilometer on Rhoda Island, Cairo

Kay C. Klinger

Version of the article suitable for citation

on ART-Dok (Heidelberg University Library)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00009827

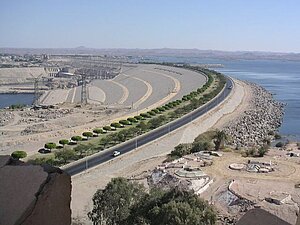

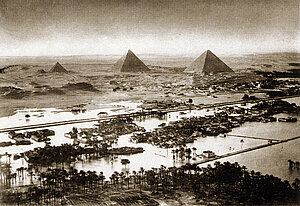

The construction of the great Aswan Dam in 1960–1970 on Egypt's southern border (fig. 1) made it possible to control the annual Nile flood that inundated the land on both sides of the river.[1] Although the flood (fig. 2) brought with it sediments that were deposited as fertile silt on the fields and enabled productive harvests – and the emergence of an ancient civilization in general – the strength of the flood has always been subject to fluctuations that could have devastating effects. Too much water swept away houses and damaged canals and monuments; too little water, on the other hand, led to failed harvests and thus to famines.[2] As it was not possible to regulate the Nile flood in Pharaonic times, Nile gauges, known as nilometers, were developed to help predict the expected amount of water.[3] In this way, appropriate precautions could be taken in a good time, e.g. securing firewood and the previous year's harvest so that they could not be swept away by the flood.[4]

In the first volume of his work "Oedipus Aegyptiacus" (Rome 1652), Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) deals with the geography of Egypt in "Syntagma I". He begins with general chapters on regional designations and the division of the country into three areas: the Theban and Memphitic regions as well as the Delta, each divided into ten districts ("nomoi").[5] The various districts are listed in tabular listing in connection with the cities belonging to the district and the respective main cult or animal cult (pp. 5–7). Kircher then deals with the thirty nomoi of Egypt one after the other. Each sub-chapter begins with a collection of the nomoi in other languages, primarily Greek, Latin and Coptic, followed by a description of specific characteristics (cults, buildings, etc.). For this purpose, he brings a diverse and multilingual collection of reports, treatises and biblical quotations that describe the respective district. Only about half of their descriptions are illustrated, usually in the form of a small square 'signet' inserted into the text block and depicting an animal or symbol specific to the nomós in question.

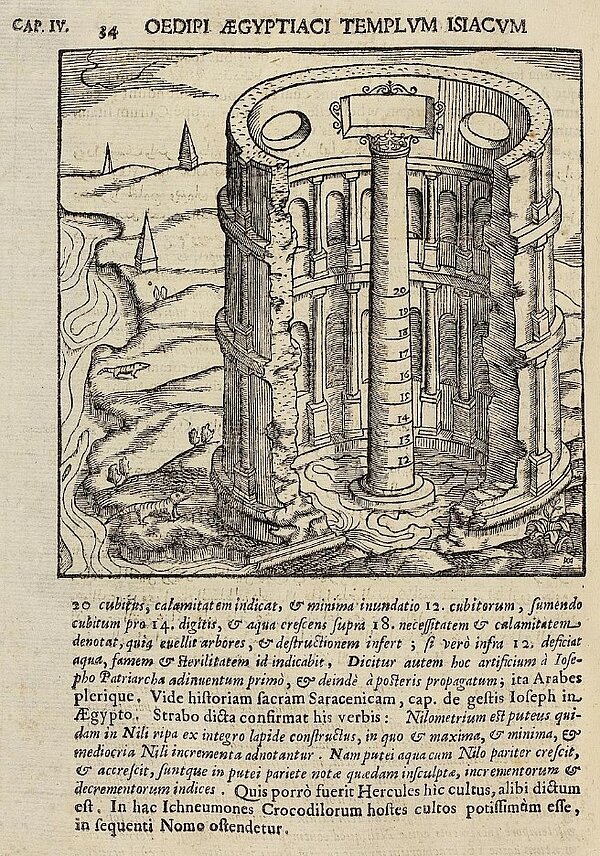

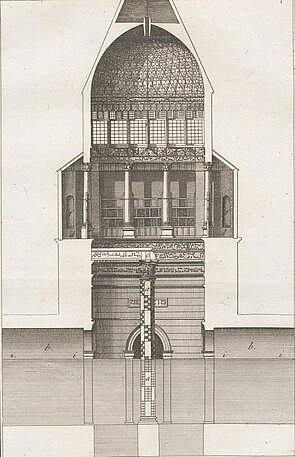

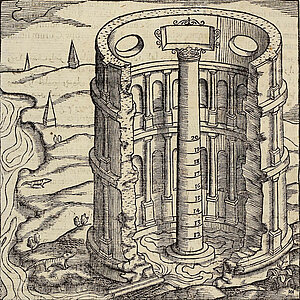

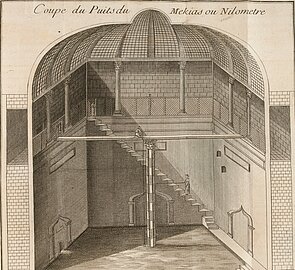

The axonometric section shows a tall, free-standing building with a round ground plan, standing on the banks of the Nile. The surrounding landscape in the background is largely undeveloped, only three pyramids can be seen in the far distance on the left. The floor of the building is covered with water, which is led there from the river through a narrow, straight and human-built channel. The walls of the building are adorned inside and outside by semi-columns on pedestals, with three storeys decreasing in height on the outside and two storeys and a parapet on the inside. Inside, semicircular niches are set into the walls between the half-columns. In the attic storey, a rectangular window decorated with volutes on three sides is flanked by two simple oval windows. In the center of the building is a free-standing column with a crown-shaped capital that rises up the entire height of the building and has markings on its shaft inscribed with the numbers 12 to 20. The building has no roof and is therefore open at the top.

In the lower right-hand corner of the woodcut there is a small signature in the form of a monogram, possibly formed from the letters M and A, which is difficult to identify (fig. 4).[6]

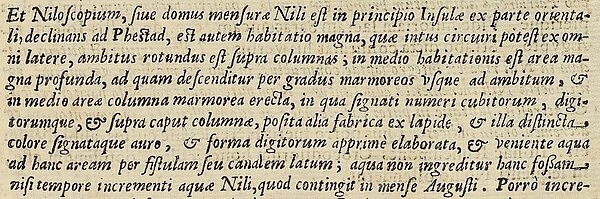

The accompanying text, citing Ptolemy and unspecified "Arabes", describes the Nilometer as standing on an island belonging to the nomos Heracleopolis. At the time, the island bore the modern name "Phestad" and was wrongly identified by some locals with the ancient sites of Heliopolis and Memphis. It is certain, however, that the Nilometer is located near Cairo and is identical to Nilopolis, a pharaonic town.[7] Kircher then quotes the description of the Nilometer from the "Geographia Nubiensis" in Arabic and adds a Latin translation:

According to the text (fig. 5), which is not immediately comprehensible, the Nilometer has the following characteristics:[8]

• located on the eastern side of an island tip, in the direction of El-Fustat

• a large building (habitatio) which can be surrounded from all sides inside

• a round gallery on columns (?)

• a large, recessed area in the middle of the building with marble steps leading down to it (all around?)

• in the center of the recess, a marble column with markings in cubits and “fingers”

• a stone element on the column, colorfully decorated and gilded

• neatly carved “fingers” (on the column?)

• water enters the area through a pipe or tunnel

• this only happens during the Nile floods in August

Continuing to quote from the same source, Kircher then goes on to discuss the significance of the Nile levels in this specific Nilometer and indicates which water levels caused problems and which amounts of water were considered ideal. He concludes his treatment of the Nilometer with a quotation from Strabo.[9]

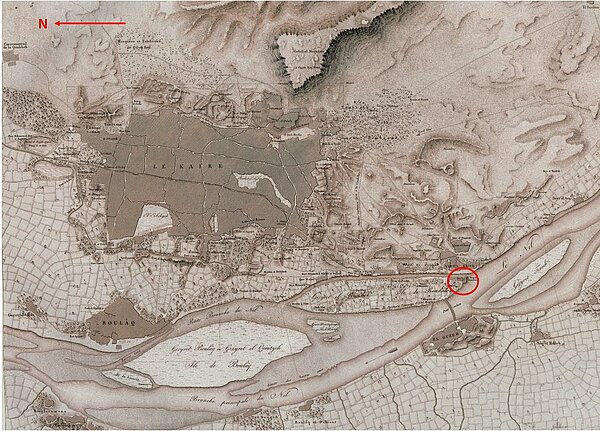

Based on the topographical information used to locate the structure, there is a consensus that the Nilometer discussed and illustrated by Kircher is a water level measuring facility that still exists today on the island of Rhoda in the heart of Cairo (fig. 6).

Before Kircher devoted himself to the subject, various Arab geographers, historians and travelers had been studying it and the inscriptions there since the 9th century AD.[10] According to his own statements, he took the description of the Nilometer from the “Geographia Nubiensis”. The work "Nuzhat al-Muschtāq fī ichtirāq al-āfāq" by the Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi (c. 1100–1166), originally from the 12th century, was first published in Latin translation by Gabriel Sionita and Johannes Hesronita under this title in Paris in 1619[11], after it had previously appeared in Rome in 1592 under the Latin title "De geographia universali" in the original Arabic.[12] However, the Latin passages quoted in "Oedipus" do not correspond word for word with Sionita's and Hesronita's version and the beginning of the Arabic quotation was probably taken by Kircher from an unknown source and placed before the direct quotation.[13] For his publication, Kircher added a Latin translation everywhere, especially for Arabic and other non-European texts. In his laudatio, Kircher's pupil Gaspar Schott (1608–1660) praised his teacher's extensive knowledge of languages. He was not only proficient in the classical languages of Latin and Greek, but also had knowledge of various Semitic languages – including Arabic.[14] From this point of view, it is conceivable that Kircher translated the Arabic source texts into Latin himself, including in the case of the Nilometer of Rhoda, either because he did not have access to Sionitas and Hesronitas version or because he felt he did not need them.[15]

It can be assumed that the text was translated once again into the colloquial language of the artist responsible for the illustration before the woodcut was finally produced according to this wording. It should be emphasized at this point that the description according to which Kircher had the illustration made was already around 500 years old in his time and that the Nilometer described was subject to structural changes over the centuries.

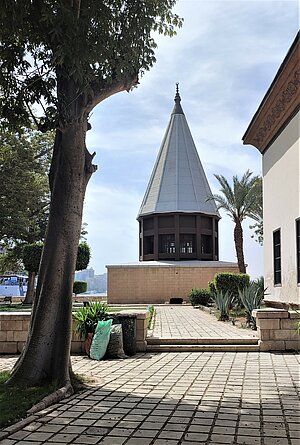

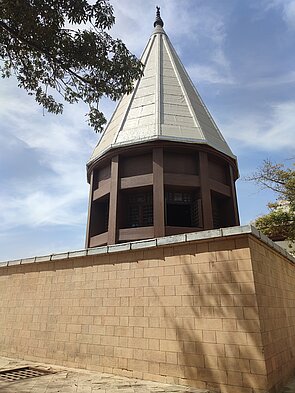

Nilometers are an invention from the early Pharaonic period, which were still in use until the 20th century. On the so-called Palermo Stone, which lists the kings in chronological order from the Predynastic period to the 5th Dynasty, in addition to information on festivals and political events, a narrow extra line also contains measurements of the water level of the Nile. The fragmentary tablet proves that the water level of the Nile was measured annually from the 1st Dynasty (3032–2853 BC) at the latest.[16] However, the Nilometer of Rhoda (fig. 7) is a building from the early Islamic period. It is not known whether there was already a measuring point at the same location in Pharaonic times.[17] Around 715 AD, under Caliph Walid ibn Abd al-Malik, a simple Nilometer was erected at the southern tip of the island, but this was rebuilt as early as 861 AD on the orders of Caliph al-Mutawakkil. Several restorations were carried out in the following centuries.[18] Due to the destruction of the dome around 1800 during the French occupation[19], the above-ground part of the building was reconstructed in the 20th century based on 18th-century architectural records by Frederic Louis Norden.[20] When the large dam near Aswan went into operation, the measuring point finally lost its function and the inlets were sealed.

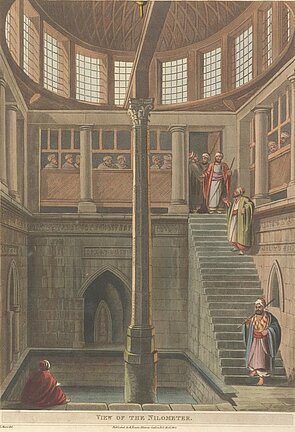

Visitors today see a free-standing single-storey building with a square ground plan. A twelve-sided wooden structure with just as many windows and a steep twelve-sided tent roof rises on top of it (fig. 8a). To the north, a few steps lead down from today's ground level to the entrance door. Behind it is a single room, in the middle of which is the 13 m deep well of the Nilometer (fig. 8b). A gallery runs around the square edge of the well and four pillars support the delicately gilded and painted dome, which is concealed on the outside by the tent roof (fig. 8c, 8d). The well has a square shape at the top, but for the lowest 2 m it is round.

It also tapers step by stept over its entire height towards the floor. A staircase running all around the walls, interrupted by a number of landings, leads down to the bottom. Large rectangular and pointed-arched niches are set into all four walls at about half height. Three openings in the east wall at three different levels were used to let in the water from the Nile, which was brought in from the river through underground channels. In the center of the shaft rises the octagonal measuring column, the shaft of which has markings at regular intervals and bears a Corinthian capital. A crossbeam extending from the eastern to the western edge of the shaft rests on it. This and the upper edge of the shaft are decorated with Kufic inscriptions of texts and suras from the Koran that focus on water and fertility (fig. 8b).[21]

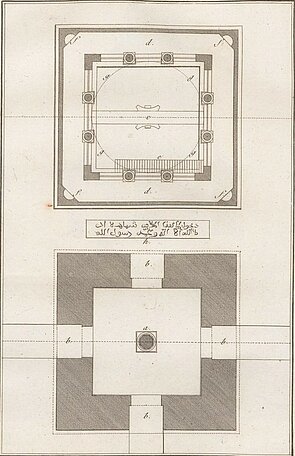

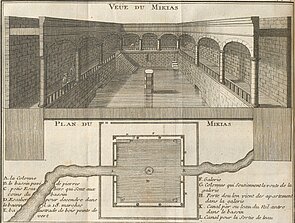

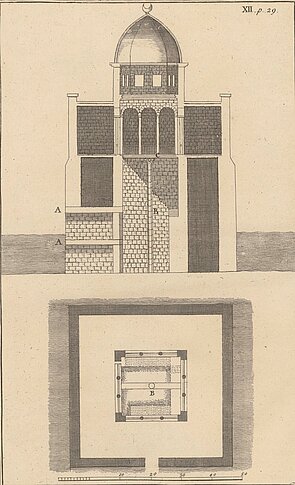

After Kircher, the Nilometer of Rhoda was drawn, painted and engraved many more times. For example, depictions by Paul Lucas (1719)[22] (fig. 9) and Richard Pococke (1743-45)[23] (fig. 10) appeared in print.

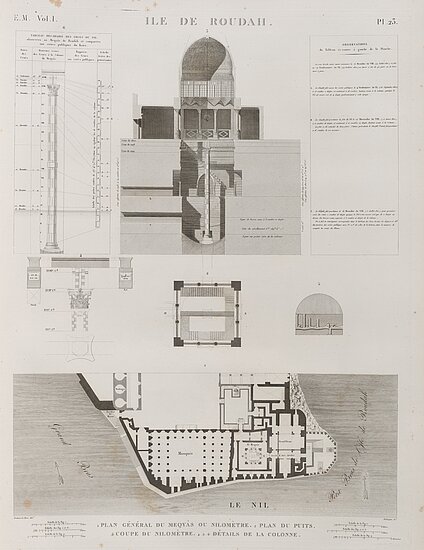

Further surveys were made by Frederik Louis Norden (1708-1742) during his trip to Egypt in 1737–38, which Karl Markus Tuscher etched for the publication of his travelogue, which appeared posthumously in two volumes in 1755 (fig. 11a, 11b).[24]

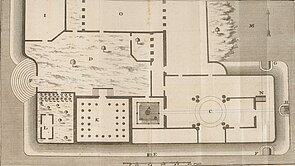

A survey of the Nilometer with a simple map of the surrounding area by Claude-Louis Fourmont (1703-1780) (fig. 12a, 12b) was also published in 1755.[25]

A: Nilometer; B: Colonnade; C: Palace of the Caliph; D: Courtyard; E: lowest channel of the Nilometer; F, G, H: inlets to the middle and upper channel; I: garden; K: mosque; N: stairway to the inlets

The building was recorded in particular detail during Napoleon's expedition in 1798–1801 and published in 1809 in the work "Description de l'Égypte".[26] Not only is the Nilometer itself reproduced there in plan, section and detail, but also a more detailed ground plan of the palace inside which it was located at the time (fig. 13).

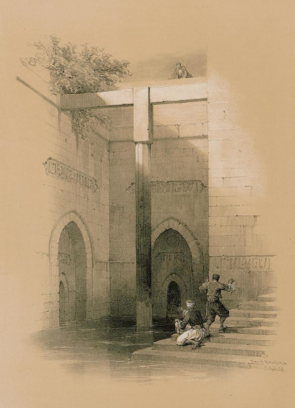

In contrast, the prints by Luigi Mayer (1755–1803),[27] which depict the gauging station in 1803 before it was partially destroyed, have a more artistic approach (fig. 14). The well-known veduta painter David Roberts created a depiction of the Nilometer in 1838,[28] when its entire above-ground structure no longer existed. Only the shaft and the central measuring column with the crossbeam were preserved (fig. 15).

However, after closer examination of the visual sources mentioned, it must also be noted that some differences and inconsistencies are noticeable: The cross-section in the "Description de l'Égypte" suggests that the gallery running around the edge of the well was of different widths, but this is not confirmed either by the accompanying ground plan or by the other diagrams. Due to a simultaneous Nile flood, it was also not possible for Norden to record the well down to the bottom, which means that the measuring column in his survey is too short. Further inconsistencies arise in David Roberts' work with regard to the structure and proportions of the staircase, which, as shown, is not comprehensible on the existing building, and the exact position of the entrance gate depicted in the "Description de l'Égypte" remains speculative. Furthermore, the overall location of the entrances to the Nilometer appears inconsistent: While Lucas' ground plan suggests a gateway in the south, Pococke places it in the middle of the north wall.

Fourmont and the "Description de l'Égypte" agree that the Nilometer could be entered from both the east and the north, but the ground plan in the "Description de l'Égypte" shows not just one, but two eastern entrances, the location of which does not correspond to that in Fourmont. Whereas in Lucas and Pococke the shaft of the Nilometer is enclosed by an arcade, Norden, Fourmont, Mayer and the "Description de l'Égypte" show a colonnade. As far as the shed roofs above the arcade in Norden's work are concerned, they also do not correspond with the other representations, in Fourmont's work the shape and design of the dome is also not comparable with the other depictions and Lucas does not depict anything at all above the arcade.[29] In Mayer's drawing, the measuring column protrudes high above the edge of the well so that the crossbeam rests on the architraves of the colonnade at both ends. As in Mayer's work, the column also bears a Corinthian capital in Norden's work and in the "Description de l'Égypte", which was replaced by a simple vertical square block in Roberts' work and is not depicted at all in Lucas' work. In addition, the border around the edge of the well is depicted differently in each illustration. There is complete disagreement regarding the number and orientation of the channels through which the Nile water was channelled into the measuring point; this may be due to the fact that most observers may have visited the structure when the shaft was more or less flooded.

It is astonishing that all the explorers and travel painters mentioned were supposedly on site and were able to see the Nilometer with their own eyes, and yet the variations in the individual illustrations are numerous. Many of the differences in the illustrations can probably be explained by the fact that they illustrate some of the structural changes that have been made to the Nilometer since Idrisi.[30] But perhaps some of the inconsistencies are also due to a lack of interest in accurate reproduction or the imagination of the respective author? It is possible that some of the diagrams were created after a single visit, while others are based on measurements of varying precision. At the very least, the contradictory alignment of the channels and the different depiction of the shaft can probably be attributed to a high Nile level. At the time of their visit, the respective explorers and travelling painters were presumably only able to use the still visible outlines of the niches and their position in relation to the Nile to determine the location of the canal openings.[31] Nevertheless, at least the basic structure of Rhoda's Nilometer is essentially the same in all the illustrations mentioned.

Let us return to Kircher, his Arabic sources and the woodcut by the unknown monogramist. Interestingly, both the present-day appearance and the depictions of the Nilometer from the 18th and 19th centuries as well as Kircher's illustration largely coincide with Idrisi's description. Nevertheless, Rhoda's nilometer is hardly recognizable in the Kircher illustration (fig. 16).

Idrisi mentions a round gallery on columns (?). This is probably the description of the colonnade shown in the building record by Norden and in the "Description de l'Égypte" and in Mayer's depiction, which once supported the dome and the roof. However, when Kircher's illustration was created, the description was obviously misunderstood and led to the interior and exterior façade being decorated with half-columns. Important features such as the square basic shape of the building above ground and the well are not mentioned by Idrisi and are therefore not depicted graphically. The fact that the Nilometer and the surrounding building are only partly above ground and mostly underground is also not mentioned. As a result, it is understandable that the Nilometer is depicted as an exclusively above-ground structure. The location of the channels is also not described in detail and is therefore assumed to be at ground level at the bottom of the Nilometer. The stairs inside the well mentioned in the text have been omitted for unknown reasons and the decorated structure at the top of the measuring column, which presumably refers to the crossbeam, is briefly described, but is only vaguely depicted in the graphic as the capital of the column. Although not mentioned by Idrisi, three windows were inserted into the attic in the woodcut. This could either be due to additional information that Kircher had obtained from other, unmentioned sources, or to the artist's imagination. In any case, it is obvious from the surviving visual information that the latter did not see the building for himself on site, but created his illustration solely on the basis of the description Kircher passed on to him.

Ultimately, Idrisi's brief description, Kircher's translation of his description into Latin and the illustrator's visualisation are all based on interpretations and sometimes also on misunderstandings, just like in a game of Chinese whispers (or the Telephone game). In a way, Heraklit's words πάντα ῥεῖ – everything flows are illustrated here: Everything is in flux and therefore changeable – in this case the human perception of a building and its mediation in images.

[1] Cf. H. Schamp, Sadd el-Ali, der Hochdamm von Assuan I, in: Geowissenschaften in unserer Zeit, 1983, No. 2, p. 57.

[2] Cf. LÄ 3 (1980) p. 82 s. v. Hunger (W. Guglielmi).

[3] According to classical authors, taxes were also based on the water level measured in the Nilometer: If the tide was high, more water reached the interior and promised a greater harvest. See also: Strab. 17, 48; Hdt. 2, 109.

[4] Cf. S. Prell, Der Nil, seine Überschwemmung und sein Kult in Ägypten, in: SAK 38, 2009, p. 214.

[5] Modern research distinguishes between the Upper Egyptian region with 22 districts and the Lower Egyptian region with 20 districts.

[6] Cf. G. Nagler, Die Monogrammisten, vol. 4, ca. 1871, p. 471, No. 1522, where three variants of the monogram are treated together and „Domenico Ambrogio, genannt Minghino del Brizio, oder ein unbekannter Formschneider“ are given as possible authors.

[7] Cf. A. Kircher, Oedipus Aegyptiacus I, Rom 1652, p. 32-33.

[8] The discrepancies in Kircher's description could possibly be clarified by a thorough comparison with the Arabic original by Idrisi. Such a text-critical examination was not possible in this article. I would like to thank Dr. Michael Marx (BBAW) for his kind advice in this regard.

[9] Cf. A. Kircher, Oedipus Aegyptiacus I, Rom 1652, p. 33-34.

[10] Cf. W. Popper, The Cairo Nilometer, Berkeley & Los Angeles 1951, p. 41-47.

[11] M. Idrisi, Geographia Nubiensis. Id est accuratissima totius orbis in septem climata divisi descriptio, continens praesertim exactam uniuersae Asiae, & Africae, rerumq[ue] in ijs hactenus incognitarum explicationem. Recens ex Arabico in Latinum versa a Gabriele Sionita & Ioanne Hesronita, Paris 1619 <https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10218990-9>.

[12] M. Idrisi, De geographia universali: Hortulus cultissimus, mire orbis regiones, provincias, insulas, urbes earumque dimensiones & orizonta describens, Rome 1592 <https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb11223705-1>.

[13] Cf. M. Idrisi, De geographia universali, Rom 1592, S. 112-113 <https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb11223705?page=200,201> und M. Idrisi, Geographia Nubiensis, Paris 1619, p. 98 <https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/view/bsb10218990?page=170>.

[14] Cf. G. Schott, Benevolo Lectori, in: A. Kircher, Oedipus Aegyptiacus I, 1652, n. p.

[15] However, his Latin translation of the Arabic text can be considered imprecise due to incorrect references and sentence turns.

[16] Cf. Urk. I, 235-249. The Palermo Stone documents the presence of a water level measuring station. However, archaeological evidence for nilometers from these times has not yet been found; the oldest currently known nilometer belongs to the Chnum temple on Elephantine and dates to the Late Period (664-332 BC) (Cf. S. Seidlmayer, Die Vermessung des Nils im Alten Ägypten, in: fundiert, Wasser, 2004, No. 2).

[17] Tabular inscriptions on the base of the "White Chapel" of King Sesostris I (12th Dynasty) in the temple of Karnak date from around 1920 BC and document the Nile levels of three Nilometers in the south and north of Egypt as well as in the so-called Per-Hapi ("House of the Nile Flood") in the region of present-day Cairo (see S. Seidlmayer, Die Vermessung des Nils im Alten Ägypten, in: fundiert, Wasser, 2004, No. 2)). At the beginning of the 20th century, Kurt Sethe identified the preserved Nilometer on Rhoda as the above-mentioned Per-Hapy, although this assumption cannot be confirmed today (see K. Sethe, Beiträge zur ältesten Geschichte Ägyptens, in: Untersuchungen zur Geschichte und Altertumskunde Ägyptens, vol. 3, 1905, p. 105).

[18] Cf. W. Popper, The Cairo Nilometer, Berkeley & Los Angeles 1951, p. 16-29.

[19] Cf. W. Popper, The Cairo Nilometer, Berkeley & Los Angeles 1951, p. 29.

[20] Cf. M. Volait, The restoration of the Muhammad Ali Mosque in Cairo, 1931-1938, in: Claudine Piaton et al., Building beyond the Mediterranean, 2012, p. 182.

[21] Cf. D. Behrens-Abouseif, Islamic architecture in Cairo: an introduction, Leiden & New York & Köln 1992, p. 51.

[22] P. Lucas, Voyage du sieur Paul Lucas, Den Haag 1720, vol. 2, p. 69 <https://www.e-rara.ch/zuz/content/zoom/14874416>.

[23] R. Pococke, A Description of the East, vol. 1, London 1743-45, pl. 12, p. 29 <https://archive.org/details/gri_33125009339603/page/n69/mode/1up>.

[24] F. L. Norden, Voyage d'Egypte et de Nubie, vol. 2, Copenhagen 1755, pl. 25; 26 <https://archive.org/details/gri_33125008624443/page/n54/mode/1up> , <https://archive.org/details/gri_33125008624443/page/n56/mode/1up>. Cf. AKL 111, 2021, 54; ThB 33, 1939, 503 et sqq.

[25] C. L. Fourmont, Description historique et géographique des plaines d'Héliopolis et de Memphis, Paris 1755, pl. 2, p. 130; pl. 3, p. 142 <https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1510888r/f179.item> , <https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1510888r/f193.item>

[26] Cf. E. F. Jomard (Ed.), Description de l'Égypte: ou, Recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l'expédition de l'armée française. Etat Moderne, Planches. Tome Premier, 1809, vol. 1, pl. 23; 53 <https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.4739#0029> , <https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.4739#0059>.

[27] L. Mayer, Views in Egypt, from the original drawings in the possession of Sir Robert Ainslie, taken during his embassy to Constantinople, London 1801, p. 12 <https://archive.org/details/gri_33125012351108/page/n21/mode/2up>.

[28] D. Roberts, The Holy Land: Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia, vol. 3, London 1849, n. p. <https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/roberts1849bd6/0040/image,info>.

[29] Lucas' accompanying report also makes no mention of a roof. It is possible that the Nile level measuring point was open at the top at the time or that Lucas omitted the depiction of the dome and the roof for unknown reasons.

[30] Popper compiled the structural alterations made to the Nilometer from 715 AD until the early 19th century. (Arabic) historians and the "Description de l'Égypte" documented some of the alterations and served as Popper's main sources. However, Popper does not mention any changes after 1801 in his publication (see W. Popper, The Cairo Nilometer, Berkeley & Los Angeles 1951, S. 16-29).

[31] Cf. W. Popper, The Cairo Nilometer, Berkeley & Los Angeles 1951, p. 40.