#5: digital meets analogue – Antiquitatum Thesaurus in Paris

Cristina Ruggero, Timo Strauch

Version of the article suitable for citation

on ART-Dok (Heidelberg University Library)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00009821

Digital projects as well as electronic data indexing and management have become an integral part of research in the humanities. The increasing number of digitized objects and of databases supports the study of heterogeneous and locally scattered material in its interconnections.

Besides the possibility to comfortably acquire information about analogue works – from graphic collections to artifacts –, digitized materials ensure a better preservation of the originals and offer technically optimal conditions to easily explore, enlarge or comparatively analyze their images on screen instead. The digitization platform DWork of the Heidelberg University Library [1] has already made available in an exemplary form many of the printed works of the 17th and 18th centuries that are central to the work plan of the Antiquitatum Thesaurus project, and further source material will follow in the course of the cooperation with the Thesaurus. In addition, the project relies on digitized volumes of drawings and printed works similarly provided by GALLICA, including several from various departments of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF). In addition, many artifacts to be catalogued by Theasurus are listed in a collection database in the département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques of the National Library of France. [2]

Despite these excellent digital working conditions, for an appropriate scientific assessment of the material it is desirable to consult at least a representative selection of the various works in the original and – when the collection contexts allow it – to compare them directly with one another. For this purpose, and in order to establish a fruitful long-term cooperation, it is also necessary to engage in a direct dialogue with the most important institutions.

The first module of our project – Egypt: In Search of Origins – is characterized by a huge number of Egyptian objects or objects considered as such. Together with the many graphic reproductions that have emerged from this subject, they are mainly related to France and especially to Paris and the institutions there, as are many collectors and their cabinets, the network within the République des Lettres and Bernard de Montfaucon – protagonist and red thread of the project with his work “L'Antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures”. The choice of the town on the Seine as the destination of our first research expedition was therefore obvious.

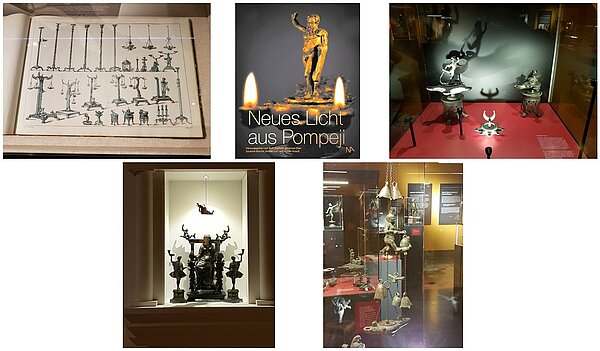

First Stage: Munich

Our study trip started in Munich with a visit to the exhibition New Light from Pompeii in the State Collections of Antiquities (Staatliche Antikensammlungen) (idea, concept and design by Ruth Bielfeld together with Johannes Eber and Peter Weidenhammer). Astrid Fendt accompanied us through the impressively designed rooms. The lucerne (oil lamps) appear in their numerous, at times extravagant guise and in different sizes in almost every collectanea on the reception of ancient objects of everyday culture: Fortunio Liceti (1577–1657), Giovanni Battista Casali (1578–1650), Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680), Filippo Buonanni (1638–1725), and many others show an exquisite and significant selection of specimens from various collections. Although the exhibits shown in Munich originate from Pompeii and thus cannot be considered direct models for the visual sources catalogued by Thesaurus, several lucerne types made it possible to draw parallels to the documents and artifacts listed in the Thesaurus (e.g. ThesaurusID 1709601). Not only the private rooms with these lighting devices used for practical purposes but also other topics, such as research on the aesthetic values of this archaeological genre or the culture of light in antiquity have been brightly addressed in the exhibition.

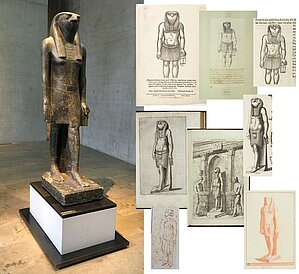

Next on our agenda was a visit of the collection of the State Museum of Egyptian Art (Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst), which houses a particularly interesting work. The anthropomorphic standing figure of the falcon-headed god Horus from the mid-14th century BC, also known as the Barberini Osiris, was unearthed in Rome in 1636 near the church of S. Maria sopra Minerva, in the area of the ancient Iseum Campense. [3] We wanted to comprehend the fascination that this statue had immediately afterwards and throughout the centuries, giving rise to nearly a dozen early modern representations (see ThesaurusID 1398304). They can be found in the works or collections of the so-called Pseudo-Duperac (1636), Alessandro Donati (1584–1640), Cassiano dal Pozzo (1588–1657), Joachim von Sandrart (1606–1688), Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680), Richard Topham (1671–1730), and Bernard de Montfaucon (1655–1741).

Paris

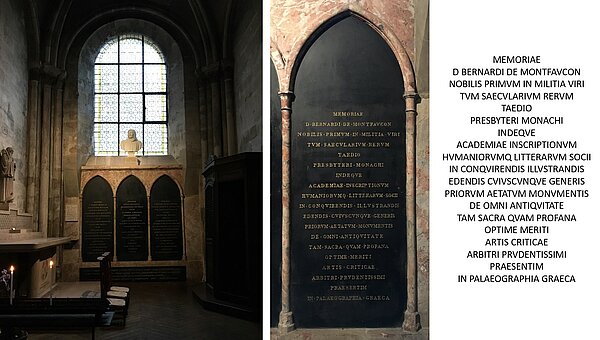

Once in Paris, the first thing we had proposed was to pay a visit to the tomb of Bernard de Montfaucon (1655–1741), who is buried in the Chapelle de la Vierge in Saint-Germain-des-Prés alongside Jean Mabillon (1632–1707) and René Descartes (1596–1650). The text of his epitaph reads:

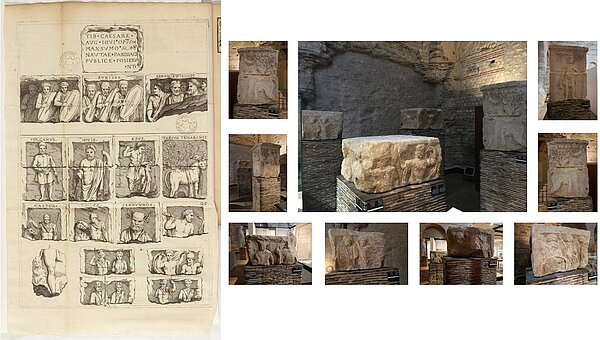

Somewhat overshadowed by a current exhibition on the Gothic in Toulouse, we were able to take a close look at the Pillar of the Nautae Parisiaci in the Frigidarium of the Baths of Lutetia, now part of the Musée de Cluny – Musée national du Moyen Âge. The four blocks with representations of Roman or Gallic deities and a dedicatory inscription, at present displayed separately, once formed a pillar in a sanctuary on the Île de la Cité and date to the 1st quarter of the 1st century AD. On site, using the alpha version of the Thesaurus database, we were able to access the earliest graphic representations from 1711 for direct comparison (cf. ThesaurusID 1672345).

However, the stay in Paris was primarily devoted to consulting BnF documents, manuscripts but also artifacts from its various departments and depots holdings.

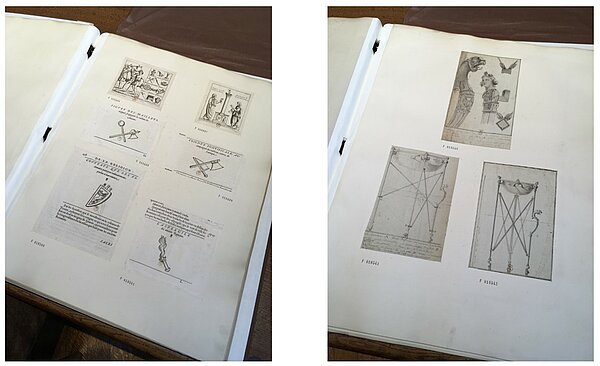

The album with drawings of objects from the former collection of Nicolas-Joseph Foucault (1643–1721) – Desseins des figures, bas reliefs et inscriptions. Recueil de Figures et autres monumens antiques – is dated between 1714 and 1719 and one of the most important sources and templates for Montfaucon. Browsing the album confirmed the heterogeneous nature of the graphic material it contains. [4] Of the about thousand objects listed in an written inventory, some two hundred and fifty bear references to drawings commissioned by Foucault. [5] The comparison of drawings executed directly on the album’s sheets, those pasted onto the album’s pages, and clippings from Montfaucon's proofs requires a closer look at the album to better understand the process in which it was produced and the relative chronology of its contents.

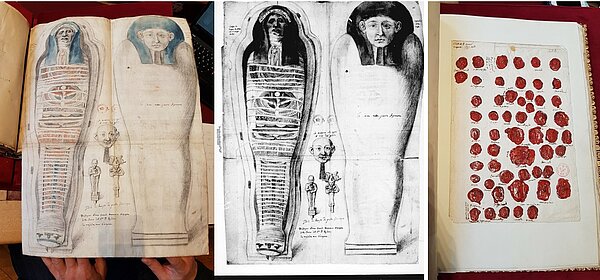

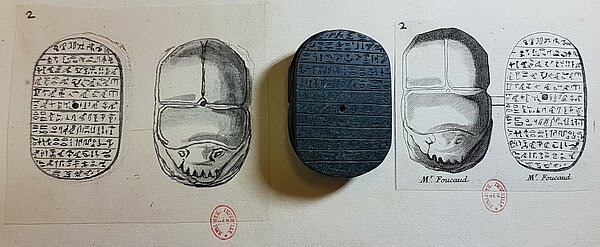

Through the generous courtesy of Mathilde Avisseau-Broustet, a unique opportunity arose during our visit to examine the fidelity of the draughtsmen, for example in the transcriptions of hieroglyphs, and the relationship in size between the reproductions and the surviving artifacts, as in the case of a heart scarab [6]:

... and a small Horus stele [7]:

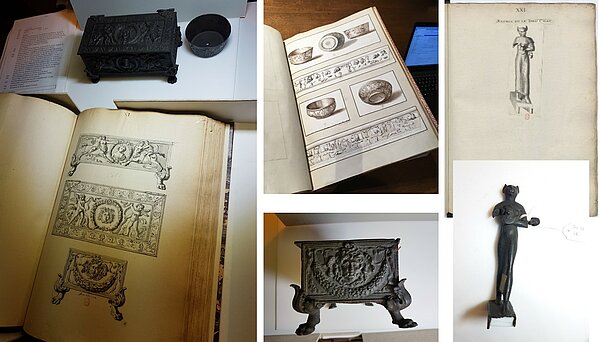

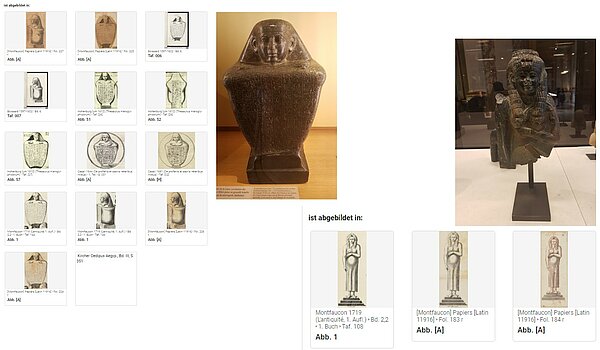

A highlight of our visit were some Egyptian objects that we had catalogued in Berlin shortly before, as well as some modern works also included in the graphic corpora because they were considered ancient originals or because their iconography was relevant to the respective discourses. While only a small selection of these artefacts are on display at the BnF Museum, we were able to take a closer look and examine several items taken directly from the BnF’s depot. These are some of the precious pieces:

- A modern box for writing utensils, which antiquarians considered an ancient incense box (acerra), from the Foucault collection (ThesaurusID 1598677) next to its reproduction in the Foucault album. [8]

- An antique bowl with Bacchic scenes (ThesaurusID 1429673) juxtaposed with drawings in the so-called Cabinet de Peiresc. [9]

- A statuette of the goddess Bastet with an aegis in front of her chest and a basket on her left forearm (ThesaurusID 1600893). It too originally belonged to the Cabinet Foucault and was graphically recorded in the Recueil. [10]

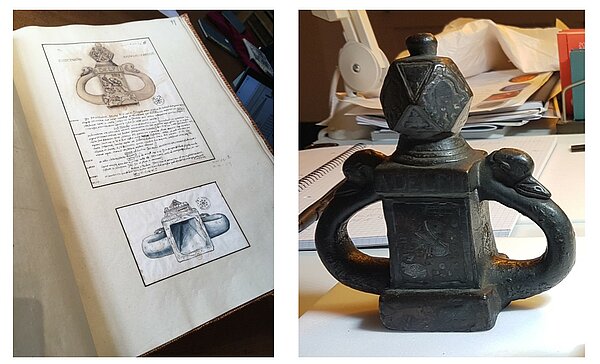

About a year ago, an enigmatic bronze knob kicked off our blog series. Two watercolor drawings in one of the two albums of the so-called Cabinet de Peiresc reproduce this curious object, which we were able to get our hands on shortly before in the Museum Department of the BnF (ThesaurusID 1315419): [11]

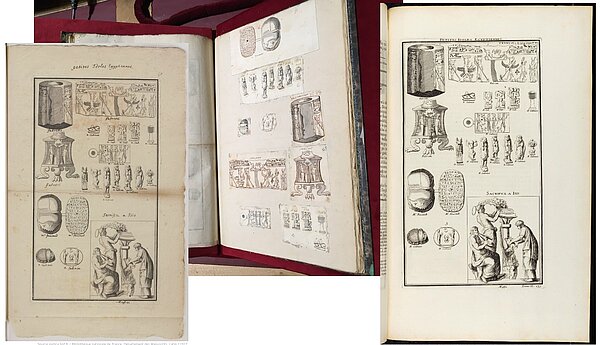

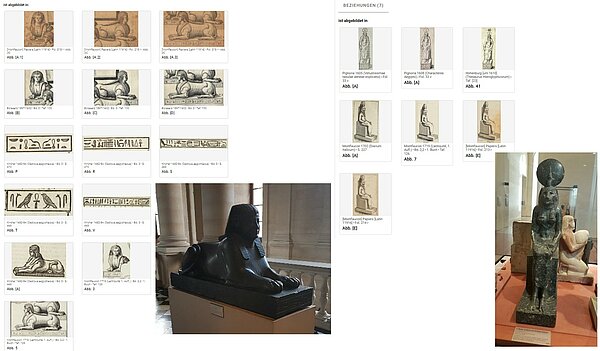

For the investigation and the understanding of the creation process of the 15 volumes of “L'Antiquité expliquée” (1719–1724), especially the so-called Papiers de Montfaucon are extremely thrilling. [12] Of the 17 albums, several contain, to variable degrees, the pictorial material that Montfaucon compiled from countless, highly heterogeneous sources and then prepared step by step for printing in collaboration with the engravers who worked for him. For example, a page in the album Ms. latin 11917 shows how a drawn copy based on the drawing of the heart scarab shown above from the Foucault collection is related by Montfaucon to other drawings of Egyptian artifacts from other sources. Bound immediately before it is a proof of the plate, on which the illustrations have been put in a different order, while the information on the origins of Montfaucon's illustrations has been added still in handwriting. On the final plate in the published first state, these are then transferred to the engraving, as are the title and the numbering of the plate.

The interrelations between the various forms of graphic reproduction and the references to the depicted artifact are presented comprehensively by the Thesaurus database.

Further volumes of the BnF, which will be catalogued for the Thesaurus in the future, come from the bequest of Nicolas Claude Fabri de Peiresc, e.g. Ms. Dupuy 667. [13] It contains numerous letters, treatises on ancient numismatics, glyptics and epigraphy, wax impressions of ancient coins and gems, as well as remarkable drawings, and can so far only be consulted online as a digital copy of a black-and-white microfilm.

The Antiquités grecques et romaines are a still largely unpublished collection of drawings and prints in the holdings of the Dép. Estampes et photograhie of the BnF. [14] It is a recent form of a paper museum in the tradition of Cassiano dal Pozzo and a specifically archaeological precursor to Aby Warburg's Bilderatlas. The extensive collection with over 2,000 graphic reproductions of antiquities of various origins has not yet been digitized at all.

The department of Egyptian art of the Louvre contains several objects that had already found their way to Europe in the period before the Napoleonic expeditions to the Nile, and which can also be found in the visual sources studied for the Thesaurus, including the two sphinxes of Nepherites I (ThesaurusID 1315329) and Achoris (ThesaurusID 1315331) as well as a seated statue of the goddess Wenut (ThesaurusID 1552188). [15]

For the musée Charles X (today's département des Antiquités égyptiennes), inaugurated in December 1827, Jean-François Champollion, who shortly before (1822) had made a name for himself by deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, was appointed director. For the very first Egyptian museum at the Louvre, he had compiled a small guide with descriptions and detailed explanations of the 5,333 monuments partially on display and completely unknown to the public: Notice descriptive des monumens égyprienns du musée Charles X... (1827). Despite its lack of illustrations, objects have since been identified and catalogued [16] to the extent that the Thesaurus was able to link and annotate them with their associated pictorial sources, including, for example, the cube figure of Petamenophis (ThesaurusID 1432981) and the statue of Cleopatra VII (ThesaurusID 1597938), which is now heavily fragmented. [17]

The conclusion of the research trip can be of little surprise: Direct observation of the objects of one's own scholarly work is the most effective way to reliable knowledge regarding size, materiality and state of preservation, and no digitization – no matter how perfect – can replace it. However, there is almost never the opportunity to view several testimonies of the past at the same place and at the same time, sometimes their preservation in two different departments of the same institution is already enough to create insurmountable hurdles. It is here, where the database, available at any time and in any place, wins with its virtual links of information on objects, persons, places and historical events, just as the Antiquitatum Thesaurus is aiming to do.

[1] UB Heidelberg: DWork – Heidelberger Digitalisierungsworkflow; http://dwork.uni-hd.de.

[2] BnF, Médailles et Antiques. Catalogue en ligne; https://medaillesetantiques.bnf.fr/ws/catalogue/app/report/index.html.

[3] Cf. Alfred Grimm: Münchens Barberinischer "Osiris". Metamorphosen einer Götterfigur, exhibition catalogue Munich 2001; https://katalog.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/titel/65646257.

[4] Paris, BnF, département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, inv. FOL RES MS-96, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b72000419.

[5] Cf. Mathilde Avisseau-Broustet: La Collection de Nicolas-Joseph Foucault (1643–1721) et de Nicolas Mahudel (1673–1747), in: Histoires d'archéologie. De l'objet à l'étude [en ligne] 2009, https://doi.org/10.4000/books.inha.2788.

[6] Paris, BnF, département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, inv. AA.Eg.40, https://medaillesetantiques.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/c33gb260r7 and Paris, BnF, département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, inv. FOL RES MS-96, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b72000419/f208.item.

[7] Paris, BnF, département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, inv. 53.237, https://medaillesetantiques.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/c33gbr819 and Paris, BnF, département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, inv. FOL RES MS-96, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b72000419/f212.item.

[8] Paris, BnF, département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, inv. Foucault.A4.Pl.XII, https://medaillesetantiques.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/c33gb24hds and Paris, BnF, département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, inv. FOL RES MS-96, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b72000419/f374.item.

[9] Paris, BnF, département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, inv. 56.358, https://medaillesetantiques.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/c33gbrv47 and Paris, BnF, département des Estampes et photographie, RESERVE AA-53-FOL, Fol. 58 r, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b104611474/f121.item.

[10] Paris, BnF, département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, inv. 53.36, and Paris, BnF, département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, inv. FOL RES MS-96, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b72000419/f192.item.

[11] Paris, BnF, département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, inv. bronze.1885, https://medaillesetantiques.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/c33gb179cb and Paris, BnF, département des Estampes et photographie, RESERVE AA-54-FOL, Fol. 99 r, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b525058020/f208.item.

[12] Paris, BnF, département des Manuscrits, Ms. latin 11904–11920.

[13] Paris, BnF, département des Manuscrits, Ms. Dupuy 667, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10032883z.

[14] Paris, BnF, département Estampes et photographie, Ga 69 Fol.–Ga 84 Fol.

[15] Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. A 27, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010009338, inv. A 26, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010007879, inv. N 4535, https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010011397.

[16] Cf. Jean François Champollion: Notice descriptive des monuments égyptiens du Musée Charles X, ed. by Sylvie Guichard, Paris 2013; https://katalog.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/titel/67432458.

[17] Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. N 93, https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010008657, inv. E 13102, https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010016440.

![Paris, BnF, dép. des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, heart scarab of green stone and Desseins des figures, bas reliefs et inscriptions. Recueil de Figures et autres monumens antiques [1714–1719], 1e armoire, no. XXIX (Photos: Cristina Ruggero)](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/b/csm_blog5_08_skarabaeus_9b05a8b770.jpg)

![Paris, BnF, dép. des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, Horus stele and Desseins des figures, bas reliefs et inscriptions Recueil de Figures et autres monumens antiques [1714–1719], 1e armoire, no. XXXI (Photos: Cristina Ruggero)](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/1/csm_blog5_09_stele_268c8686d4.jpg)