#13: What a state!? The “Medaillons du Roi”

Lea Küster

Version of the article suitable for citation

on ART-Dok (Heidelberg University Library)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00009829

Bernard de Montfaucon’s (1655–1741) Supplément au livre de l'antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures from 1724, like his well-known book series L'antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures (1719), depicts a large number of different antiquities. Once again, the approximately 425 engravings in the five Supplément volumes show a wide range of different types of objects: in addition to prominent sculptures such as the Laocoon group, reliefs, altars, architecture, gems and coins are also depicted. In the Supplément volumes, Montfaucon also organised his objects thematically according to ancient deities and mythological figures, customs and funerary rites, everyday objects, military equipment and other functional objects, following the approach he had already tried out in the previous L'Antiquité books. He labelled all the individual illustrations with the respective graphic source or an indication of the origin of the object shown.

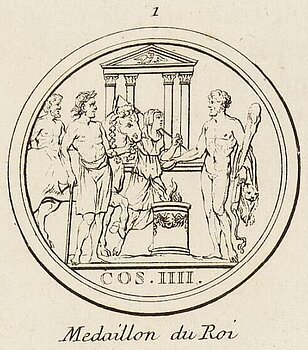

There is one source work in particular that is frequently referred to in Montfaucon’s Supplément volumes: Among 151 of all coins depicted in the Supplément, the indications “Medaillon du Roi”, “Medaillons du Roy” or variants thereof can be found (fig. 1 and 2; ThesaurusID 1573885 and ThesaurusID 23924346). [1]

In this case, “Medaillons du Roi” can be understood as a synonym for both source work and provenance, as Montfaucon's reference points to a set of plates commissioned by Louis XIV, which reproduces a selection of Greek and Roman coins from the extensive royal collection. As the work is not accompanied by a title page, a preface or a more detailed description, and there is no recognisable thematic sorting of the coin images, such as Montfaucon pursued in his works, it is not clear from the engravings themselves what criteria were used to select the objects for the Medaillons du Roi. This ambiguity inherent in the Medaillons du Roi is already apparent in the naming of the work, as there is still no standardised title for the publication. In addition to the most common auxiliary title Medaillons du Roi and Montfaucon's various citations, one can also find names such as Medaillons antiques du Cabinet du Roy, Medaillons du Cabinet du Roi or Suite des medaillons du cabinet du Roy.

The history of the creation of the Medaillons du Roi is just as erratic as the work's title. Alongside other illustrated volumes on, for example, the royal tapestries (Tapisseries du Roy), the sculpture collection (Statues du Roy, antiques et modernes) or vases and busts (Termes, bustes, sphinx et vases du Roy), the Medaillons du Roi also became part of the large-scale publication project Cabinet du Roi. [2] An exact dating for the Medaillons du Roi has not yet been established. The project for the coin volume was probably conceived and initiated in 1667 by Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683), then finance minister of the French crown under Louis XIV. Payment receipts from 1672 to the French engravers Gilles Jodelet de La Boissière (active between 1660 and 1680) and Pierre Giffart (1643–1723) provide concrete indications of the time when the Medaillons du Roi were created. [3] The latter can only be connected to the work on the basis of the aforementioned payment receipts, whereas Boissère’s signature can be found on five engraved plates. [4] The last traceable payment to the two artists was made in 1679. The project of the Medaillons du Roi itself was cancelled for the time being after Colbert's death in 1683. [5]

The final version of the so-called Cabinet du Roi ultimately comprised twenty-three volumes, the aim of which was to present and glorify the reign of Louis XIV in all its many facets and to present the king as a great patron of the fine arts. [6] Ancient coins were given a special role in this context. Under Louis XIV, the royal coin collection had grown enormously, as the young king had inherited the extensive coin collection of his late uncle Gaston d'Orleans (1608–1660) – along with an increased fascination and interest in antiquities. [7] In addition, ancient coins served as a model for another of Colbert’s projects. Together with the Petite Académie (also Académie Royale des Inscriptions), a new institution founded in 1663, he had set himself the task of immortalising the legacy of Louis XIV in the form of medals and bringing out a corresponding publication. [8] The coin-like format of the bronze or gold medal was chosen with care: not only did ancient coin depictions of Roman emperors have a glorious reputation, but the metal pieces had also proven to be an appropriate medium for the dissemination of political self-portrayal thanks to their robustness and longevity. The medal thus had a promising potential, which the scholars around Louis XIV wanted to utilise specifically for their mission of disseminating the royal gloire. [9] It was not uncommon for ancient coin originals to serve as a source of inspiration for the newly designed medals about the life of Louis XIV and his political achievements. [10] Although the Medallions du Roi were less prominently subject to such a political agenda, they were just as clearly part of the French crown's ceremonial toolbox.

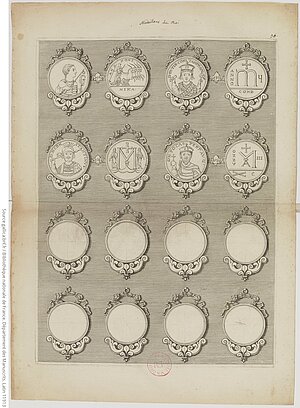

Today, 25 copies of the Medaillons du Roi can be found in the holdings of public libraries worldwide. [11] These copies are not only the source of the varying titles, the volumes are also characterised by a variance in content. Of the 25 copies, 23 contain 41 plates, one contains 36 plates and one only 29 plates. The formal structure of the plates themselves is generally consistent: the background of the individual plates, measuring 50.5 x 35.5 cm, is formed by fine, carefully drawn horizontal lines, which achieve an almost cloth-like effect in their overall appearance. [12] On this background, the antique pieces from the Cabinet du Roi are depicted in a grid of four by four coin images with elaborate framings (fig. 3; ThesaurusID 1619858).

The frames usually bear the Latin material designation “AE” and are decorated with a heraldic fleur-de-lis, indicating that the coins belong to the royal collection (fig. 4; ThesaurusID 23957714). [13]

Typically, two neighbouring illustrations show the obverse and reverse of the same coin, which are identified as belonging together by a ‘ligature’. In these standard cases, eight coins are depicted per plate (fig. 3). However, there are also individual coin images – i.e. obverse or reverse alone. In addition, ligatures can also be observed across the line break in individual coin images arranged on the right edge of the plate. Finally, there are cartouches that have been left completely blank, mostly in isolated cases, but sometimes distributed several times across the panel, sometimes covering entire lines and in one case even half a plate (fig. 5; ThesaurusID 1619889).

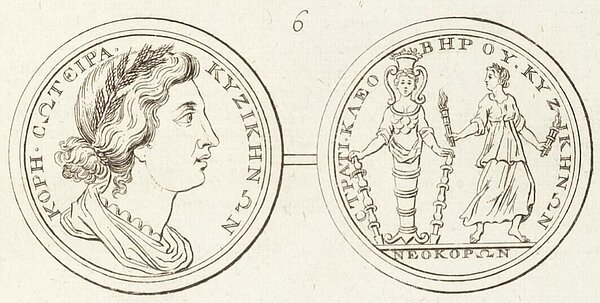

This formal heterogeneity alone reveals a certain lack of systematisation and consistency within the Medaillons du Roi. In addition to this design of the plates, which is nevertheless mostly consistent in its basic features, there are other differences between the various copies of the Medaillons du Roi that are not immediately recognisable. One of the most significant differences is the way they are numbered. Some of the Medaillons du Roi copies with fewer than forty-one plates feature a numbering of individual coin illustrations beginning with 1 and ending with 299. A complete copy of this form with 36 plates is now in the Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. [14] Within this edition, for coins whose obverse and reverse are depicted together, the illustration number is placed in the ‘ligature’ between the two views (fig. 6; ThesaurusID 23956818). For depictions of only one coin view, the image number is located at the top centre between the coin image and the framing cartouche (fig. 7; ThesaurusID 23957251).

In contrast, the issues with forty-one leaves have plate numbering from 1 to 41, which – due to the smallness of the numbers – is rather inconspicuous in the top centre of all plates, while the numbering of the individual coin images has been removed (figs. 8 and 9; ThesaurusID 1619863 and ThesaurusID 23957960).

![8 Medaillons du Roi [2nd state], pl. 6, detail (Photo: Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/3/csm_blog13_abb_08_9f5c92a0f6.jpg)

![9 Medaillons du Roi [2nd state], pl. 6, fig. [G] (Photo: Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/8/csm_blog13_abb_09_f4c1985bbc.jpg)

On some plates, however, traces of the former illustration numbering can still be recognised, which indicates the revision of the copper engraving plates used and establishes a chronological order of the editions, thus marking two different states of the Medaillons du Roi (figs. 10 and 11; ThesaurusID 23878835 and ThesaurusID 1619884). The version with a smaller number of plates and with the original illustration numbering can thus be understood as the first state and the more extensive edition with the later introduced plate numbering as the second state. [15]

In addition to the altered numbering, the two states differ in another aspect concerning the individual coin images themselves, as in the second state a large number of these can also be observed to have been subtly reworked. This involved changes to the motifs of the coin images as well as corrections to the coin legends. Surprisingly, the motivation behind this reworking remains mostly unclear. The changes to the coin images in particular are usually incomprehensible when looking at the original objects.

For example, the individual illustration of a Greek coin reverse presents a prize table, the feet of which have the shape of lion paws, set with a prize crown, palm branches and two purses. In the first state of the Medaillons du Roi, the scene is depicted frontally, whereas in the second state, the two rear table legs and a top view of the table top have been added, so that the arrangement is now depicted axonometrically (figs. 12 and 13; ThesaurusID 23878958 and ThesaurusID 1620284). The coin type to which both depictions refer is more similar in appearance to the first state of the Medaillons du Roi, as only two table legs are visible there as well (fig. 14; ThesaurusID 1617622). [16] Thus, the reworking does not appear to have been a reasonable, object-orientated correction, as the reworked state is considerably further from the original.

In the context of Montfaucon's Supplément, it is these revisions of the illustrations that help to identify the state of the Medaillons du Roi used by him as the model for his copies. A first indication is given in the preparatory materials for the L'Antiquité books, the so-called Papiers de Montfaucon. Here, in one of the albums (Paris, BnF, Ms. Latin 11913), a single sheet of the Medaillons du Roi was glued in between numerous hand drawings and labelled “Medaillons du Roi” by hand (fig. 15). The illustration numbers on this plate show that it is a sheet from the first state. This fact already proves that Montfaucon had access to the much rarer version of the Medaillons du Roi, at least in this case.

A systematic comparison between the Supplément and the Medaillons du Roi illustrations allows us to conclude that the Montfaucon illustrations are related to the first state. The obverse of another Greek coin depicted in the Medaillons du Roi, for example, shows the head of Kore Soteira in profile. She wears an ear of grain in her curly hair, which is pinned up in a plait. Around her neck she has draped a pleated scarf from which the base of a necklace peeps out. [17] In the first state of the Medaillons du Roi, the ribbon has a wavy shape, whereas in the second, reworked state it has been remodelled into a jagged shape (figs. 16 and 17; ThesaurusID 23957152 and ThesaurusID 23957718).

In addition, the Kore Soteira wears an earring in the second state – unlike in the first. The legend on the edge of the coin has also been changed: where it begins with the word “KORH” in the first state, the “R” has been corrected to a “P” in the second state, so that it now correctly reads “KOPH”. Minor changes were also made to the reverse of the coin: The cult image of the Ephesian Artemis on the left edge of the coin bears a calathos filled with leaves on its head in the first state, which was changed to an architectural structure in the second state.

A look at Montfaucon's coin depiction shows a clear correspondence with the depiction in the first state, as Montfaucon also shows the female profile with a wavy collar and without an earring (Abb. 18; ThesaurusID 23923825). The reverse also resembles the variant from the first state of the Medaillons du Roi in all relevant respects. However, the scholar did not miss the opportunity to replace the incorrect spelling “KORH” with the correct form “P”. [18]

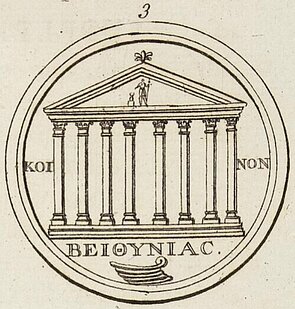

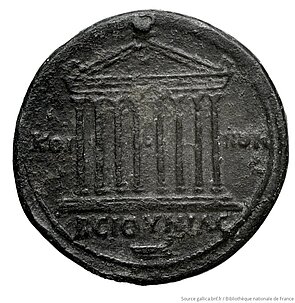

The image of another Greek coin reverse reveals Montfaucon's reference to the first state of the Medaillons du Roi even more obviously: In the centre of the image is the frontal view of an octastyle temple, whose column capitals and bases have been elaborately rendered. In the centre of the pediment stands a figure with a spear in their left hand and an altar to their right. The legend ΚΟΙ-ΝΟΝ ΒΕΙΘΥΝΙΑϹ is arranged around the temple. A ship's prow is placed below the temple and legend (fig. 19; ThesaurusID 1573817). The same structure can also be found in the coin depiction in the first state of the Medaillons du Roi (fig. 21; ThesaurusID 23960378). However, the second state of the Medaillons du Roi is different (fig. 22; ThesaurusID 23960382): here the prow of the ship has been removed and the figure in the pediment replaced by a wreath of leaves, which clearly distinguishes the depiction from the first state and from Montfaucon – and also from the actual model, the reverse of a coin from Bithynia (fig. 20; ThesaurusID 1617603). [19]

In Conclusion

There is still little clarity about the exact circumstances surrounding the creation of the two Medaillons du Roi states. With regard to the history of their creation, it can at least be emphasised that the intention behind the creation of both graphic series was not of a purely academic, truth-seeking nature. Rather, the aim was to emphasise the preciousness and rarity of the pieces and thus strengthen the prestige of the royal collection and interest in it. The reworking of the illustrations therefore did not distort the message or the idea behind the publication. Nevertheless, it is surprising that this particular aspect of the publication history of the Medaillons du Roi has not been recognised in the still rather limited research literature. The contemporary numismatist Lorenz Beger (1653–1705) is already witness of this shift in focus to the second state. In his publication Numismata Moduli Maximi vulgo Medaigloni ex Cimeliarchio Ludovici XIV (Berlin 1704), he copied the forty-one engraved plates of the second state, whereby the new engravings were less skilfully executed than the original. [20]

Why Bernard de Montfaucon chose the first state as the model for his Supplément au livre de l'antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures cannot be answered definitively either. In view of his position as president of the newly christened Académie royale des Inscriptions et Médailles from 1719, it can be assumed that he at least had access to, if not a good overview of, the royal Cabinet du Roi and all its publications. [21] The question remains as to whether Montfaucon was aware of the differences between the Medaillons du Roi editions and therefore deliberately opted for the state that more accurately reflects the antique objects. Another, less favourable assumption could be that the remaining copies of the first state of the Medaillons du Roi were considered obsolete due to the second state that had since become available and that the recycling of the outdated plates, as Montfaucon did in preparation for the Supplément, was therefore a natural and logical action. Whether or which of these options comes closest to the truth remains to be seen. What is certain, however, is that the Medaillons du Roi offer plenty of potential for further, exciting explorations. The high artistic standard with which the individual panels were designed, as well as the clearly intentional composition of the objects depicted alone offer reason to pay further attention to this illustrated series – this article has hopefully provided some inspiration for this.

[1] Cf. de Callataÿ, François: “Bernard de Montfaucon et les monnaies antiques”, in:L' antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures de Bernard de Montfaucon, Bordeaux 2021, vol. 2, p. 441.

[2] Other volumes in the Cabinet du Roi series included, for example, architectural views or illustrations of the great festivals organised by King Louis XIV.

[3] Cf. Wellington, Robert: Antiquarianism and the Visual Histories of Louis XIV, Farnham/Burlington 2015, p. 103.

[4] Plates 7, 9, 10, 12 and 15 are signed by the engraver once with “De la Boissiere”, once with “De Laboisiere fecit” and three times with “De la Boissiere fecit”.

[5] Cf. Sarmant, Thierry: Les intendants et gardes du Cabinet des médailles des origines à 1753, Paris 2007, URL: https://comitehistoire.bnf.fr/intendants-gardes-cabinet-m%C3%A9dailles-origines-1753 (last visited on 29 April 2025).

[6] Cf. Wellington 2015, p. 83.

[7] Cf. Wellington 2015, pp. 80–81. With the addition of Gaston d’Orleans’ collection, the coin cabinet comprised around 7,000 pieces at the beginning of the 1660s and grew steadily from then on. By the end of Louis XIV’s reign, the royal coin cabinet contained around 15,000 pieces. Cf. Veillon, Marie: “La science des Médailles antiques sous le règne de Louis XIV”, in: Revue numismatique, 6e série, vol. 152, 1997, p. 364.

[8] This project was developed under the working title Histoire métallique. The resulting publication Médailles sur les principaux événements du règne de Louis le Grand was published in 1702.

[9] Cf. Wellington 2015, pp. 40–41.

[10] One of the Petite Académie’s main tasks, for example, was the cataloguing of ancient coin legends. The repertoire of numismatic vocabulary resulting from this work was used specifically to create the legends of the medallions of the Histoire métallique. Cf. Wellington 2015, p. 58.

[11] At this point, I wish to emphasise the thorough research work of Emily Grabo, who located and analysed all the editions. In addition to the library holdings, two further copies of the Medaillons du Roi are listed in the sales catalogues of the auction houses Sotheby's and Kolbe & Fanning.

[12] The measurements come from the auction lot of Kolbe & Fanning, whose carefully researched description provided important information for the cataloguing: https://bid.numislit.com/lots/view/1-M8WPP (last visited on 16 May 2025).

[13] Cf. Wellington 2015, p. 85.

[14] Digital copy: hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p15150coll3/id/14846 (last visited on 4 May 2025). However, seven plates (plates [3], [8], [11], [14], [18], [22] and [28]) are included here, which contain coin images without numbering, i.e. the 299 numbered coin images can be found on 29 plates. A corresponding copy of this size can be found in the Biblioteca nazionale Braidense in Milan.

[15] In addition to the fairly standardised (normal) editions, which hardly differ from one another in structure and size, there are also hybrid forms of the Medaillons du Roi. One such copy can be found in the Oldenburg State Library. Digital copy: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:45:1-778042 (last visited on 5 May 2025).

[16] A coin of the described cn type 8039 (https://www.corpus-nummorum.eu/types/8039) is in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, inv. no. IFN-8586548.

[17] With the described attributes the coin can be identfied with RPC type IV.2, 710 (temp.) (https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/coins/4/710).

[18] This approach is not an isolated case: Montfaucon often corrected inscriptions and legends in his publications, which points to his own self-conception as an expert on Greek antiquity. He had already put this to the test in his 1708 publication Palaeographia graeca. Arpad M. Nagy analyses another case using the example of a magical gem in his essay “The Long Biography of a Kassel Anguipes Amulet: A Case Study in Textual Criticism”, in: Gemmae, vol. 8, 2026 (in preparation).

[19] The coin is not definitely identified, but the known specimens of the type RPC 1018 (e.g. https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/coins/3/1018; last visited on 26 May 2025) all show the same attributes on the reverse. The obverse of the coin in question is not depicted by Montfaucon. However, it shows the differences between the first and second state just as impressively: Hadrian wears a laurel wreath in the second state, which is not yet present in the first state.

[20] A digitised copy is available online at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek; digital copy: https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/details:bsb10633933 (last visited on 5 May 2025).

[21] In 1714, the Petite Académie, which had previously been promoted under Colbert, was renamed the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres.

![3 Medaillons du Roi [2nd state], pl. 1 (Photo: Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)](/fileadmin/_processed_/e/5/csm_blog13_abb_03_b34249c5ca.jpg)

![4 Medaillons du Roi [2nd state], pl. 1, fig. [A] (Photo: Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)](/fileadmin/_processed_/1/8/csm_blog13_abb_04_c639153f6a.jpg)

![5 Medaillons du Roi [2nd state], pl. 32 (Photo: Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/f/csm_blog13_abb_05_0781b14774.jpg)

![6 Medaillons du Roi [1st state], pl. [1], fig. 1 (Photo: Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery)](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/6/csm_blog13_abb_06_31ff2545fa.jpg)

![7 Medaillons du Roi [1st state], pl. [6], fig. 40 (Photo: Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery)](/fileadmin/_processed_/2/d/csm_blog13_abb_07_9b49f77d86.jpg)

![10 Medaillons du Roi [1st state], pl. [27], detail (Photo: Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery)](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/4/csm_blog13_abb_10_6323fd65ba.jpg)

![11 Medaillons du Roi [2nd state], pl. 27, detail (Photo: Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/f/csm_blog13_abb_11_935d4fc992.jpg)

![12 Medaillons du Roi [1st state], pl. [21], fig. 167 (Photo: Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery)](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/8/csm_blog13_abb_12_58440bd945.jpg)

![13 Medaillons du Roi [2nd state], pl. 21, fig. [H] (Photo: Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)](/fileadmin/_processed_/1/f/csm_blog13_abb_13_4026b15d2d.jpg)

![16 Medaillons du Roi [1st state], pl. [1], fig. 5 (Photo: Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery)](/fileadmin/_processed_/e/3/csm_blog13_abb_16_3704c4e3ca.jpeg)

![17 Medaillons du Roi [2nd state], pl. 1 fig. [E] (Photo: Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/f/csm_blog13_abb_17_60248094f4.jpeg)

![21 Medaillons du Roi [1st state], pl. [4], fig. 22 (Photo: Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery)](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/0/csm_blog13_abb_20_ff50b24130.jpeg)

![22 Medaillons du Roi [2nd state], pl. 4, fig. [F] (Photo: Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/6/csm_blog13_abb_21_23f2e9acb0.jpeg)