#9: Hands up! – "perperam incisor fecit" – The Sucellus in Petau‘s Portiuncula

Cristina Ruggero

Version of the article suitable for citation

on ART-Dok (Heidelberg University Library)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00009825

The first illustrated catalogs of a private antiquities collection

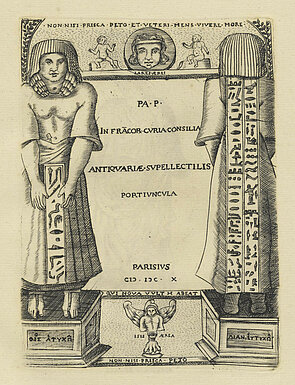

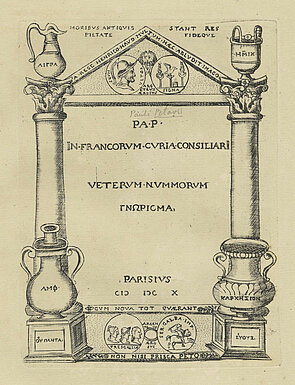

The Antiquariae Supellectilis Portiuncula [1] (a selection of ancient artifacts) and the Veterum Nummorum Gnōrisma [2] (Roman and early medieval coins) are considered the first known illustrated printed catalogs of a collection of antiquities. The objects illustrated therein belonged to Paul Petau (1568–1614), an advisor to the Parliament of Paris during the reign of Henry IV (1553–1610).

The title pages of both volumes bear the place and year of publication (PARISIVS – M DC X) but no publisher, so that Petau can be assumed to be the publisher himself. There are no accompanying commentary texts in the catalogs, the plates are not numbered and the only information is provided by a few inscriptions at the top and bottom edges or in the middle of the plates, which contain evidence on the name, material, and place of display or storage of the objects in the collection. Occasionally there are year references documenting more recent discoveries or mostly finds made after 1610, the supposed year of publication of the catalogs. The frontispieces themselves are remarkable for their presentation (fig. 1–2): Erudite mottos together with some staged artifacts from Petau’s collection provide the prelude to the printed works, which represent a turning point in the history of antiquarian culture both in terms of significance and form and were described as “a monument of useful labor”.[3]

Petau played an important role in French political life at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, especially in connection with the events before and after the assassination of King Henry IV in 1610, but he was also a man of universal talents, a scholar who frequented the circle of Nicolas Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580–1637), an avid collector of small antiquities and French medieval coins, and a keen bibliophile.

The reception of Petau’s collection catalogs is limited and dates mostly to the 18th century. Occasionally, individual objects from his collection have been reproduced elsewhere, such as the Satyr Mother with Child (now in the BnF, inv. no. 55.114), which is depicted half a century later (1671) in a printed work by Charles Patin with two new engravings in oblique view.[4] Nevertheless, a detailed study of Petau‘s collection and its illustrations has yet to be carried out. A project hosted at the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte in Munich in collaboration with the Heidelberg University Library and financed by the Thyssen Foundation [5] aims to reconstruct the collection on the basis of the two catalogs and to publish an annotated edition of it. One of the main tasks and prerequisites for further studies of both the collection and the illustrated catalogs is to consider different variants of the first bound copies with the date of 1610, in terms of both the number of plates and their order.[6]

The Sucellus in Petau‘s Portiuncula

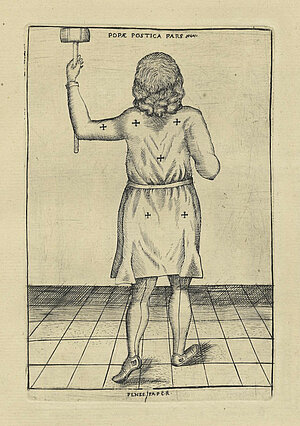

Of the approximately 500 artifacts depicted—antiquities and coins—one small bronze statuette stands out in particular, the graphic reproduction of which underwent several reworks and which Petau referred to as "POPA ÆREVS" (fig. 3). The popa played an important role as servant in religious animal sacrifice rituals. In reality, the model for our graphic is the Gallo-Roman god Sucellus [7] and Petau's misunderstanding is certainly due to the very similar iconography of the two figures.[8] The whereabouts of the depicted statuette in Petau’s possession is still unknown, but a similar bronze statuette from Lausanne (fig. 4), together with the graphic, gives us an idea of its appearance.[9]

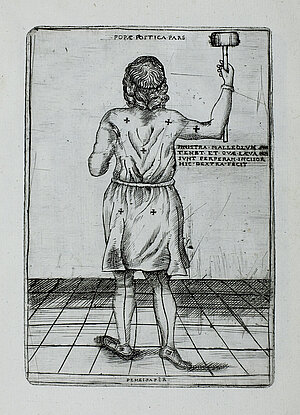

The depiction in Petau’s Portiuncula shows a middle-aged man standing in the pose of Jupiter with a full beard and long, curly hair that falls to his shoulders. He is wearing a sleeved robe (Gallic skirt) dotted with stars that ends just above his knees and tight pants. The robe is open at the front and the two overlapping halves are held together by a belt from which two loops are pulled. The lower corner of the overskirt is folded over to reveal that the inside of the fabric also has the cross pattern. Leg garments cover the muscular, slightly splayed legs, which suggest a walking posture, with the body leaning on the right leg while the left is held clearly backwards. The Sucellus wears flat low shoes on his feet, which become one with the legging.[10] The left arm is raised bent at the side of the body and the left hand holds a wooden hammer with a shaft reaching down to the elbow. The right arm is at the side and the forearm, which is bent forwards, was already broken off in Petau’s time. The figure gives the impression of standing in an enclosed space, although this is not clearly defined: while the floor with its rectangular pattern is depicted in central perspective, the background remains unstructured and neutral. A thin line frames the scene.

In the catalog, the Sucellus is depicted in two views, one from the front and one from behind. The accompanying inscriptions on the panels read POPA ÆREVS (top) and PENES PA(ulum P(etavium) C(onsiliarium) R(egium) (bottom) for the front view, and POPÆ POSTICA PARS (top) and PENES PA(ulum P(etavium) C(onsiliarium) R(egium) (bottom) for the view from behind.

Correction and suggested addition

The depiction of an ancient object from different perspectives slowly begun to establish in prints from the mid-16th century onwards, both south and north of the Alps [11], and is not an isolated case within the catalogs of Petau’s collection either. It also appears on the plates with the Satyr Mother and Child [12], the Egyptian statue of the frontispiece (fig. 1), the Ushebti [13], the Isis lactans [14], as well as some small objects (fibulae, grave goods, oil lamps, signacula [15]) and coins [16]. However, different decisions were made both in the depiction of the artifacts from different perspectives or from different sides and in their arrangement on the plates. The Sucellus and the Satyr Mother with Child were given more space than other antiquities by depicting the front and back of each on a separate sheet. The front and rear views of the Egyptian statue of the frontispiece and the Ushebti, on the other hand, are depicted side by side on the same plate. This is also the case with the Isis lactans, which is shown frontally and in three-quarter view. Objects of everyday culture are also depicted from different angles, side by side and together with other artifacts. The coins follow a different tradition: the obverse and reverse are always placed next to or on top of each other.[17]

The examination of several copies of the Portiuncula—62 have been identified so far—has revealed that the illustrations of the Sucellus have an eventful genesis, a fact that is useful for a relative chronology of the different variants of the catalog with the antiquities from Petau’s collection. There are four different illustrations of the Sucellus—two front and two back views. Why, can be easily explained.

The sequence of their creation could be as follows:

The first engraving (fig. 5) of the Sucellus shows him from the front in his real, partly fragmentary state, i.e. without the right forearm. Probably at the same time, the plate with the reverse was made (fig. 6), which—presumably due to the engraver's carelessness—shows several errors at once. In the depiction of the Sucellus from behind, the raised left arm was erroneously reproduced on the right—and in the same position as in the front view—i.e. without taking into account the rotation of the body. Accordingly, the position of the legs has also been depicted incorrectly. The set-back left leg, which is on the right-hand side of the picture in the front view, is also shown on the right-hand side of the sheet, as is the raised arm in the rear view.

The mistake was noticed and pointed out in an inscription added later, which only comments on the most obvious error—namely the incorrect depiction of Sucellus' raised right arm—, while the equally incorrect depiction of the outstretched leg remains uncommented:

SINISTRA MALLEOLVM

TENET ET QVAE LÆVA

SUNT PERPERAM INCISOR

HIC DEXTRA FECIT [18]

The plate with the incorrect depiction of the rear view of Sucellus and the remark always appears together with the plate showing the front view with the missing forearm in the copies seen so far. These are the Portiuncula exemplars from the Staats- und Stadtbibliothek in Augsburg, the Bibliothèque jésuite des Fontaines in Lyon, the Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek in Göttingen and the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel.

After the mere written rectification, it was apparently decided to engrave a new plate with the correct position of the raised arm and outstretched leg (fig. 7).

However, a direct comparison of the two engravings shows clear differences beyond the principal corrections, which may be due to the execution of the new plate by a different artist. Differences can be seen in the following details: in the rendering of hair and curls; in the way the hand is closed around the shaft of the hammer; in the guidance, length and end point of the hammer shaft, with the hammer head touching the upper edge; in the less rich folds of the robe; in the somewhat narrower hips of the man; in the smaller feet in perspective and in the less detailed rendering of the shoes; in the cleaner lines of the ground and in the overall cleaner state of the plate.

Such an intervention in an already engraved plate, i.e. the addition of a text to explain a fact, is used a second time in the illustration of the Sucellus, this time together with a graphic addition to the figure in front view. The new printed state (fig. 8) shows a suggestion for completing the missing right forearm of the figure. The wrist and the hand with the vessel (olla) are shown visibly separated from the rest of the arm to illustrate a potential restorative intervention or a possibility of the original appearance.[19]

Interestingly, Petau’s proposal is based on a comparison with another similar specimen, i.e. in an effort to make a coherent “restoration”, as he emphasizes in the inscription:

BRACHII PARS QVAE

POPAE N(ost)RO DEEST

A NON DISSIMILI

TIBI EXHIBETVR [20]

Inexperience, haste or negligence?

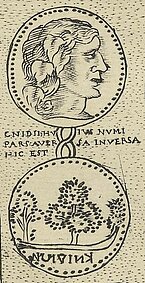

Whatever the cause, the artist made a similar mishap with another reverse. It is a Greek coin minted in Knidos, the reverse of which is depicted upside down (fig. 9). Also in this case the effort was made to point out the error with an inscription:

CNIDII HVIVS NVMI

PARS AVERSA INVERSA

HIC EST [21]

As a comparable coin from the BnF (fig. 10) shows, the supposed trees are in fact grapes, just as they actually hang on the vine. The vine motif is echoed in the wreath of vine leaves surrounding the head of the figure depicted in profile on the obverse. However, in this case the grapes could have been misunderstood as trees or shrubs.

So, who is to blame for these errors and responsible for the commentary texts?

It is not possible to say with certainty who the engraver of the Portiuncula or Gnōrisma catalogs was. The signature of the engraver, the little-known François Rousset, appears in only three places, namely in the portrait of Petau (F. Rousset Sculp. Paris) [22], which is usually bound in at the beginning of some Portiuncula volumes, and further in the Gnōrisma catalog on the plate with the coin of Chlotarius (F R SCVLP) [23] and on the plate with the title OBOLI ET CERATIA (F. ROVSSET SCVLPSIT) [24]. The latter is only included in a few variants and in the copies analyzed so far always in connection with the Sucellus without a added forearm and with the false rear view. It can therefore be assumed that Rousset was responsible for all the engravings before and around 1610, even if some features could indicate that a second artist may have been involved.[25]

The comments can be attributed to Petau. Adding notes in the margins or even annotating graphics is probably due to his bibliophile mentality. In fact, it is not unusual to find marginalia in manuscripts belonging to his library[26]

Conclusion

Soon after the invention of printing, it became common practice to record errors in the texts in a separate list—corrigenda or errata—, which is usually found on the last sheet of a book in order to avoid a costly reprint. In the case of printed images, one sometimes finds instead the variant of pasting over the incorrect engraving with corrected one.[27]

The fact that Petau had the image with the rear view of Sucellus re-engraved shows that he was obviously too embarrassed by the errors it contained to simply excuse them with an inscription and instead accepted the cost of producing a new engraving.[28] The situation was different with the Greek coin from Knidos: here he left it with the explanatory inscription, as the error seemed less serious to him in this context and because it would probably have been too costly to engrave or print a new plate with all the coins and inscriptions.

The topic addressed here would merit a much more detailed discussion. However, it will suffice here to recall two further—albeit later—examples in which the text or an inscription serves to correct an error or explain restoration additions.

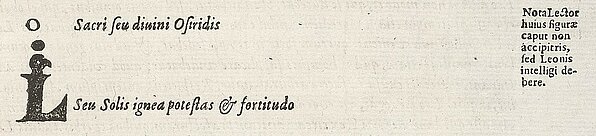

Firstly, I refer to Athanasius Kircher and the marginalia to a figure that was probably derived from a hieroglyph on obelisks (fig. 11). Kircher writes that the reader should imagine the head of the figure not as a bird but as a lion: “Nota Lector huius figurae caput non accipitris, sed Leonis intelligi debere.”[29]

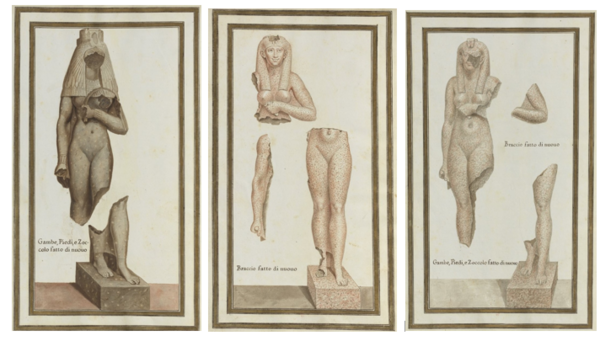

On the other hand, I am thinking of the watercolor drawings that Francesco Moratti made in connection with the restoration of five Egyptian statues that were found in the Vigna Verospi in Rome in 1710. Interestingly, he documents the restoration steps by specifying which parts were added to the statues of Tuja, Arsinoe II and an Egyptian princess (figs. 12–14), next to which one reads "Gambe, Piedi, e Zoccolo fatto di nuovo" or "Braccio fatto di nuovo".[30]

However, her we are already a century after Petau, when the awareness of philologically correct restoration, and above all its documentation, was slowly beginning to establish itself. This makes Petau’s desire for accuracy and coherence in the second decade of the 17th century all the more extraordinary.

I thank Elena Vaiani and Ulrich Pfisterer for the joint discussions and for their suggestions.

In the original version of this article, the statuette of a Satyr Mother with Child mentioned in the fourth paragraph was still identified with a specimen in the Louvre (inv. no. OA 6413). However, the identity of the sculpture illustrated by Petau with the object in the BnF is certain due to its matching state of preservation. The article was updated on 6 May 2025.

[1] Pa. P. In Fra[n]cor[vm] Cvria Consilia Antiqvariæ Svpellectilis Portivncvla, Parisivs 1610 (https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.62115).

[2] Pa. P. In Francorvm Cvria Consiliari[i] Vetervm Nvmmorvm Gnōrisma, Parisivs 1610 (https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.62116).

[3] Charles Isaac Elton, The Great Book-Collectors, 1864, pp. 261-2. Online Project Gutenberg.

[4] Cfr. Charles Patin in Imperatorum Romanorum Numismata Ex Aere Mediae Et Minimae Forma, Argentinae 1671, pp. 163–164 and plate Post paginam 164 A. A reception of the complete catalogs can be found in Albert-Henri de Sallengre—the Dutch historian—who included Petau's books in his publication Novus thesaurus antiquitatum Romanarum..., Hagae Comitum 1716—1719, 3 vols.; II, 1718, pp. 997—1050 (reprint 1735). Based on a copy of the Portiuncula with the portrait of Rousset from 1609, he had the plates recreated by the Dutch engraver Frans van Bleyswick (1671–1745), who compiled four plates from Petau’s catalogs on one sheet. In 1719–24 Bernard de Montfaucon occasionally mentioned Petau in his L'Antiquité expliquée. The sucellus is illustrated in the Supplément to vol. 2, pp. 81–2 pl. 24, where the added hand is reproduced without accompanying text (https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.59328#0156). This was followed in 1757 by a new edition published in Amsterdam with the title Explication De Plusieurs Antiquités: Représentées en plus de 500 Figures sur 47 Planches in-quarto, parfaitement bien gravées – A Amsterdam: Chez Jean Neaulme, Libaire, 1757 (https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.66768#0009). Even if we do not know who the spiritus rector was, it was certainly someone who came into possession of the copper plates. A portrait of Paul Petau from 1618 by the artist Isaac Briot opens the volume, followed by a list of the antiquities but not the coins. In this edition, a numbering of the plates has been added.

[5] “I desire nothing but ancient things” – Paul Petau (1568–1614): ancient culture, national identity and religious devotion: https://www.zikg.eu/forschung/projekte/projekte-zi/paul-petau.

[6] Paul Petau – digital: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/en/petau/collection/catalog.html.

[7] Salomon Reinach, Antiquités nationales. Description raisonnée du Musée de Saint-Germain-en Laye, Paris 1894, pp. 18ff; Marcel Chassaing, Une passion: l’archéologie. Le Dieu au maillet, Presses de l'Imprimerie Rozé, 1986; Árpád M. Nagy, „Sucellus“, Lexicon Iconographicum Mithologiae Classicae / LIMC, VII, 1994, pp. 820–823; Manfred Kotterba, SUCELLUS UND NANTOSUELTA. Untersuchungen zu einem gallo-römischen Götterpaar in den Nordprovinzen des Imperium Romanum, Diss. Uni Freiburg WS 1999/2000 (urn:nbn:de:bsz:25-opus-74446); On the identification as Sucellus, see also Ingo Herklotz, "Vätertexte, Bilder und lebendige Vergangenheit. Methodenprobleme in der Liturgiegeschichte des 17. Jahrhunderts", in: Visualisierung und Imagination. Materielle Relikte des Mittelalters in bildlichen Darstellungen der Neuzeit und Moderne, ed. by Daniela Mondini and Matthias Noell (Göttinger Gespräche zur Geschichtswissenschaft, 25), 2 vols. Göttingen 2006, I, pp. 215–51, here pp. 228–9 and note 19.

[8] Some significant examples can be found in the BnF, Département des Monnaies, Médailles et Antiques, but cataloged under the term “Dispater”.

[9] Felix Stähelin, „Denkmäler und Spuren helvetischer Religion“, in: Anzeiger für Schweiz. Altertumskunde, 26 (1924), no. 1, pp. 20–27, here p. 23 and pl. 1 (https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-160358).

[10] Annemarie Kaufmann-Heinimann, „Ikonographie und Stil. Zu Tracht und Ausstattung einheimischer Gottheiten in den Nordwestprovinzen“, in: M. Denoyelle, S. Descamps-Lequime et al. (eds.), Bronzes grecs et romains, recherches récentes. Hommage à Claude Rolley, Paris 2012 [OpenEdition 05.12.2017: https://books.openedition.org/inha/7253.

[11] On the subject of the double view of antique objects in printmaking cf. Ulrich Pfisterer: „Wie man Skulpturen aufnehmen soll“: Der Beitrag der Antiquare im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert, Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net-ART-Books, 2022 (FONTES: Text- und Bildquellen zur Kunstgeschichte 1350—1750, vol. 93). https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.1016

[12] Portivncvla, op. cit., note 1: https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.66768#0019 und https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.66768#0021.

[13] Portivncvla, op. cit., note 1: https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.66768#0033.

[14] Portivncvla, op. cit., note 1: https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.66768#0035.

[15] Portivncvla, op. cit., note 1: https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.66768#0047, https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.66768#0049.

[16] Gnōrisma, op. cit., note 2: https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.66768#0059.

[17] On the subject cf. supra Pfisterer 2022, op. cit., note 11.

[18] Translation by the author: “He is holding the hammer in his left hand and the engraver has incorrectly rendered on the right what is on the left".

[19] This proposal to add the missing hand is mentioned again in the introduction to the 1757 edition: "6. Un Popa (e) de bronze, représenté de face, tenant un maillet de la main gauche, & privé de la main droite; mais, en place de laquelle, on en voit une autre que l’on a substituée à celle qui lui manquoit", quoted from Explication De Plusieurs Antiquités, op. cit., note 54, p. 6, no. 6.

[20] “The part of the arm that is missing from our Popa is shown to you here after a not dissimilar [statuette]”, translation according to Ulrich Pfisterer, "Rom, wie es war und wie es ist": Die Erfindung der Vorher-Nachher-Illustration in der Frühen Neuzeit, Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net-ART-Books, 2023 (FONTES: Text- und Bildquellen zur Kunstgeschichte 1350—1750, vol. 96). https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.1234, p. 44, where other examples of this so-called 'addition with distance' are also discussed, such as the marginal drawings and notes on a plate with the armored statue of an emperor from Cavalieri's Antiquarum statuarum tertius et quartus liber of 1594; cf. Ulrich Pfisterer: Die Kunst der Übersetzung. Pierre Woeiriot, Giovanni Battista Cavalieri und die Antike in Frankreich, in: Pierre II. Woeiriot de Bouzey: Antiquarum statuarum urbis Romae liber primus (um 1575), ed. by Ulrich Pfisterer, Heidelberg 2012, pp. 113–229, here pp. 168–170.

[21] Translation by the author: “The backside—the reverse—of this coin of Knidos is inverted here”.

[22] Portivncvla, op. cit., note 1: exemplar from the Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel: http://www.virtuelles-kupferstichkabinett.de/de/detail-view.

[23] Gnōrisma, op. cit., note 2: exemplar from the Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augusburg: https://www.google.de/books/edition/Veterum_nummorum_gn%C5%8Drisma/JpllAAAAcAAJ?hl=de&gbpv=1&dq=inauthor:%22Paul+Petau%22&printsec=frontcover.

[24] Ibd.

[25] An investigation of the artist's name and attribution is planned as part of the project. Cfr. note 6.

[26] On Petau’s library and manuscripts cf. L. Auvray, “Sur le classement des manuscrits de Petau”, in: Le Bibliographe moderne, ann. 7 (1903), pp. 334–336; Hippolyte Auber, “Notices sur les manuscrits Petau conservés à la bibliothèque de Genève (fonds Ami Lullin)”, in: Bibliothèque de l'École des Chartes, 70 (1909), pp. 247–302; Karel Adriaan de Meyier: Paul en Alexandre Petau en de geschiedenis van hun handschriften (voornamelijk op grond van de Petau-handschriften in de universiteitsbibliotheek te Leiden), Leiden 1947.

[27] An in-depth study of this procedure is still missing. In a later work by Edme-Sébastien Jeaurat, Traité De Perspective A L'Usage Des Artistes..., Paris 1750, for example, one can see how false engravings were systematically pasted over [https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.9041].

[28] In Giovanni Battista de Cavalieri, Antiquarum statuarum urbis Romae Primus et secundus liber..., Rome 1585, for example, some plates are exchanged in comparison to the first edition published between 1652 and 1670, without it being clear why [https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.745]. Cfr. Thomas Ashby, "Antiquae Statuae Urbis Romae", in: Papers of the British School at Rome, IX (1920), no. 5, pp. 107–158; Pfisterer 2012, op. cit. as note 20.

[29] Despite the error, the same illustration is reused two more times in the same book, but without the corrective explanation. Cf. Athanasius Kircher, Obeliscvs Pamphilivs…, Rome 1650, p. 289 (https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.12#0353), p. 147 und p. 440.

[30] Translation by the author: „Legs, feet and base redone” or “Arm redone”, from: Dissegni di cinque Statue Egizzie donate al Campidoglio della Santita di N. S. Papa Clemente XI, Rom, around 1714 (https://db.antiquitatum-thesaurus.eu/object/1314440).