Project

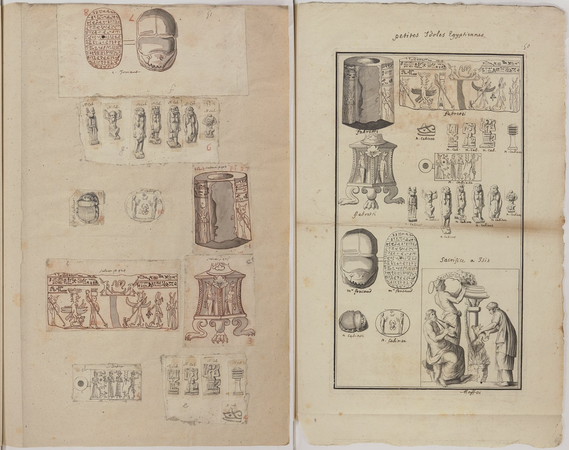

‘Antiquity’ is the reference for all subsequent epochs in many respects. The respective notions and concepts of ‘antiquity’, however, vary considerably and can in any case not be reduced to one single guiding concept of the Greco-Roman past: How ‘antiquity’ was understood with respect to time and space, what was regarded as the concrete focus, what were considered to be canonical storylines, works, and values, and how they were respectively received could vary considerably at different times, in different places, and in different knowledge contexts. Europe’s interests in its own ‘antiquities’ – as well as those of other regions of the world – were not uniform at any point in time. Attempts to understand, indeed construct ‘antiquity’ were – and continue to be made – from the respective present. Based on these ‘antiquities’ shaped by the respective contemporary contexts and expectations, what arises is a quite wide range of notions of antiquity, at which the twenty-first century looks back and to which our own present time contributes. The project consequently also does not assume the existence of one contemporary definition of ‘antiquity’, but instead occupies itself with materials and visual sources that were treated under the classification ‘ancient’ in the seventeenth and eighteenth century.

From this broad perspective, it is possible to recognize a particular importance of the recording and handing down of antiquities in images in the Europe of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, since during this period:

- The tensions between normative and plural understandings of antiquity were rising;

- The mobility of ancient relicts and their medial transformations—and in particular the visual documentation of them—reached a new level;

- Long-lasting differentiations of the history of knowledge with respect to the study of antiquity, archaeology, and art history occurred.

The examination of ancient artefacts and the visual ‘processing’ and dissemination of them were decisive factors that informed the world of images, as well as the understanding and handling of images and artefacts in the early modern period in general. Despite all the engagement with this complex of materials thus far, it will also continue to represent a central, vital challenge for all future examinations of this time. With its fundamental broadening of the material basis for research on ancient artefacts and images of them in the early modern period, the Antiquitatum Thesaurus project opens up and calls for new research perspectives and contributes to a revising of traditional canons and assumptions.

The investigation of visual sources and the course of the work plan connected with it are organized based on a combination of geographical, chronological, and material criteria. The most extensive visual thesaurus on antiquity of the early modern period, Bernard de Montfaucon’s fifteen-volume L‘Antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures (1719–24), is drawn on as a basis for the setting of focuses, and reference is thus made at the same time to an historical perspective that anticipates current interests in many respects: The view is thus oriented towards the entire Mediterranean region and Europe north of the Alps – from Asia Minor and Egypt to the Iberian Peninsula and England. It goes back, particularly in Egypt and Etruria, prior to Greco-Roman culture, and concludes on the other end in late antiquity, with the first visual references to Christianity as a state religion. No differentiation is made – as was largely customary in the early modern period prior to Winckelmann – between (high) art and other artefacts; a multifaceted and comprehensive material basis is thus incorporated, with coins, gems, and handcrafted objects of everyday use. By including, among others, with Pier Leone Ghezzi’s collection of drawings, another ‘comprehensive’ compendium of images, the project on its part, however, also critically contextualizes Montfaucon’s historical criteria and puts them into perspective.